International Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology

Soil Health and Carbon Stock Enhancement through Fruit Tree-based Agroforestry in the Degraded Lands of Central Kashmir Himalayas

1MSc. Student, Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Skuast-k, Shalimar, J&K, India

2Professor and Head, Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Skuast-k, Shalimar, J&K, India

3Professor, Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Skuast-k, Shalimar, J&K, India

4Associate Professor, Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Skuast-k, Shalimar, J&K, India

5PhD Scholar, Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Skuast-k, Shalimar, J&K, India

Author and article information

Cite this as

Fayaz B, et al. Soil Health and Carbon Stock Enhancement through Fruit Tree-based Agroforestry in the Degraded Lands of Central Kashmir Himalayas. Int J Agric Sc Food Technol. 2026; 12(1): 001-007. Available from: 10.17352/2455-815X.000230

Copyright License

© 2026 Fayaz B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Agroforestry has emerged as a sustainable land use system capable of enhancing soil health and mitigating climate change through carbon sequestration. The present study investigates the influence of fruit tree-based agroforestry systems on soil physico-chemical properties and carbon stock dynamics in comparison to sole cropping systems. Results revealed a significant improvement in soil quality under agroforestry, marked by decreased bulk density, pH, and electrical conductivity, alongside enhanced organic carbon, available nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and soil moisture. These improvements are attributed to continuous litterfall, root turnover, and better ground cover from tree-crop interactions. Simultaneously, agroforestry treatments demonstrated a higher total carbon stock across biomass (above and below ground), soil, and crops. The highest tree carbon density (8.71 t ha⁻¹) and total system carbon stock (52.88 t ha⁻¹) were recorded under apricot-based intercropping (Apricot + Rajmash), significantly surpassing the control treatments. Soil carbon stock was also notably greater under agroforestry systems, likely due to increased organic inputs and improved microclimatic conditions. These findings confirm that agroforestry not only enhances soil fertility but also contributes substantially to atmospheric carbon capture, making it a viable strategy for climate-resilient agriculture in the Himalayan region.

Agroforestry, a time-honored land-use practice in rural landscapes, integrates trees with crops to meet the growing demand for timber, fuelwood, fodder, and food while simultaneously enhancing ecological resilience. As a multifunctional system, agroforestry provides a buffer against climatic uncertainties and ensures a stable and diversified income for farmers [1]. Owing to India’s vast agro-climatic diversity, a wide range of agroforestry models have evolved, varying by region and resource availability [2]. However, accurately quantifying the spatial extent of agroforestry systems remains challenging. Current estimates suggest that approximately 25.31 million hectares, or 8.2% of India’s geographical area, is under agroforestry [3,4].

Globally, agroforestry occupies nearly 823 million hectares of land [5], and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that around 600 million hectares of degraded or idle croplands and pastures hold potential for transformation into productive agroforestry systems [6]. In India, increasing tree density on farmlands contrasts with declining forest cover, reinforcing agroforestry’s role in landscape restoration and sustainable resource use. Agroforestry significantly contributes to natural resource conservation, especially soil and water, by reducing erosion, moderating soil temperature, enhancing biological activity, and improving soil structure and fertility [7]. Merging forestry and agricultural technologies, it creates land-use systems that are not only diversified and productive but also ecologically sustainable and economically viable [2].

Among the various models, the fruit tree-based agri-horticultural system has gained prominence for its dual role in food security and income generation. This system integrates annual or perennial crops with fruit-bearing trees, effectively utilizing vertical and temporal space. Due to the short juvenile phase, high market value, and nutritional benefits of fruits, this system is especially attractive to small and marginal farmers [8]. It also enhances land productivity and optimizes the use of natural resources, making it ideal for resource-limited regions.

Moreover, integrating fruit, fodder, and timber species in mixed cropping systems is less risky than monoculture plantations, and it supports higher per-unit productivity, greater carbon sequestration, and better environmental quality. Tree components act as long-term carbon sinks by locking atmospheric CO₂ in biomass and soil, thus mitigating the effects of climate change. Simultaneously, the increased green cover and biodiversity enhance ecological services while supporting rural livelihoods [9]. In essence, agroforestry presents a sustainable alternative to conventional monocropping, offering significant ecological, economic, and climate-related benefits. Its relevance is particularly critical in the context of climate change mitigation, soil health restoration, and rural income diversification, especially in fragile ecosystems such as the Indian Himalayas. The present study aims to evaluate the role of fruit tree–based agroforestry systems in improving soil health and enhancing soil carbon stocks on degraded lands of the Central Kashmir Himalayas.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in the experimental field of Division of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, Ganderbal, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences & Technology of Kashmir (J&K) at 340 16ʹ 46ʹʹ N and 740 46ʹ 18ʹʹ E with an elevation of 1790 m (5872 feet) above mean sea level. The climate varies considerably with the altitude. It is mild and salubrious in the lower elevations but very cold in the higher elevations. Average minimum and maximum temperature varies from -5.4 to 38 °C.

Experimental methodology

Experimental details:

Treatments:

Seed sowing:

Harvesting of the crops

First harvesting of Rajmash was done in June, followed by the second in September, and harvesting of moong was done in the month of October.

Details of observation recorded

Physico-chemical characteristics of soil: Before laying out the experiment, random soil samples were collected from the depth of 0-20 cm from different spots, and the composite sample for each replication was prepared, which was analyzed for various soil characteristics in order to get information about the physico-chemical properties of the soil. After the experiment, the samples from each plot were again drawn and analyzed for various characteristics by the standard methods.

Methods employed to determine physico-chemical properties of soil:

g) Soil moisture (%)

The soil moisture content was determined gravimetrically. Before laying out the experiment, random soil samples were collected up to a depth of 20 cm, using an auger, and the composite sample was prepared. The composite sample was dried at 105 ºC till constant weight, and the soil moisture content was calculated as follows:

After the experiment, the samples from each plot were again drawn, and soil moisture (%) content was determined.

h) Soil bulk density

Bulk density is the ratio of the oven-dry mass of the solids to the volume (the bulk volume includes the volume of the solids and of the pore space) of the soil. It was analyzed following the weighing bottle method. A measuring cylinder of 100 ml was weighed and filled with soil, with continuous tapping of the bottom of the cylinder until a soil volume of 100ml was obtained. Then the weight of the cylinder containing soil was recorded. The procedure was replicated thrice, and the average weight was taken. The bulk density of the soil samples was calculated by the formula:

Carbon stock

a. Stem biomass:

Fruit Trees:

Y= exp{-2.4090+0.9522 ln(D2HS)} [15]

Where,

Y= Biomass per tree in kg

D= collar diameter of fruit trees

H= Tree height in cm

S= Wood density (g cm-3)

b. Wood density (g cm-3)

The wood density was calculated following the procedure prescribed by Bhatt and Toderia [16].

Wood density = Mass/volume.

c. Estimation of the biomass of the canopy

Canopy Biomass = Crown Volume x Specific gravity

The vol. occupied by the crown was estimated by

d. Crown volume (m3)

The Crown volume was calculated following the procedure prescribed by Avery and Burkhart [17].

Where,

CV= Crown volume (m3)

Db= Diameter (m) at crown base

L= Crown length (m)

e. Specific gravity:

The stem cores were taken to find out specific gravity, which was used further to determine the biomass of the stem using the maximum moisture method [18].

Where,

Gf = specific gravity based on gross volume

Mn = weight of saturated volume sample

Mo = weight of oven-dried sample

Gso = Average density of wood substance equal to 1.53

f. Fruit biomass t ha-1

The fruit samples (1 kg) were sun-dried for 4 to 5 days, followed by oven drying at 60ºC till constant weight. Dry weight of the fruit samples was recorded in grams and then worked out in t ha-1.

Tree Biomass = Stem Biomass + Canopy Biomass + fruit biomass

g. Estimation of below-ground biomass

Below ground biomass = Above ground biomass x 0.33 [19]

Total biomass = Above-ground biomass + below-ground biomass.

h. Estimation of Carbon Density

C (t ha-1) = Total biomass (t ha-1) x 0.5 (IPCC, 2006)

i. Soil carbon (t ha-1) = [(soil bulk density (g cm-3) x (soil depth (cm) x C (%)] x100 [20].

j. Total carbon pool of system (t ha-1) = crop carbon density + tree carbon density + soil carbon.

Statistical analysis

All recorded data on soil physico-chemical properties (pH, electrical conductivity, soil organic carbon, available N, P, and K, soil moisture, and bulk density), biomass components, and carbon stock parameters were subjected to statistical analysis following the procedures described by Gomez and Gomez [21]. The experiment was laid out in a Randomized Block Design (RBD) with eight treatments and four replications.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test the significance of treatment effects on the measured variables. Treatment means were compared using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at the 5% level of significance (p ≤ 0.05). Standard error of mean (SEm) and critical difference (CD) values were calculated wherever treatment effects were found significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using R statistical software.

The experimental data about soil health parameters, biomass accumulation, and carbon stocks were analyzed statistically using analysis of variance (ANOVA) appropriate for a Randomized Block Design (RBD). The significance of differences among treatment means was tested at the 5% probability level. Wherever significant differences occurred, treatment means were separated using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Statistical computations were performed using R software as outlined by Gomez and Gomez [21].

Results

Effect of agroforestry systems on physico-chemical properties of soil

The results indicated that fruit tree–based agroforestry systems significantly influenced soil physico-chemical properties compared to sole cropping systems (Tables 1-3). Parameters such as bulk density, soil pH, electrical conductivity, soil organic carbon, available nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and soil moisture showed marked improvement under agroforestry treatments.

Soil bulk density

Agroforestry plots recorded significantly lower soil bulk density at harvest (1.29–1.31 g cm⁻³) compared to sole cropping systems (1.33–1.34 g cm⁻³) (Table 1). Among treatments, the lowest bulk density was observed under Apricot + Rajmash (T3), while the highest was recorded in sole Moong and Rajmash plots (T7 and T8).

Soil pH and electrical conductivity

Soil pH and EC values decreased under agroforestry systems compared to open field conditions. The minimum soil pH (6.61) and EC (0.21 dS m⁻¹) were recorded under Apricot-based agroforestry treatments, whereas sole cropping treatments showed relatively higher values (Table 1).

Available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium

Available N, P, and K increased significantly under agroforestry systems at the time of harvesting. Maximum available nitrogen (361.23 kg ha⁻¹), phosphorus (17.43 kg ha⁻¹), and potassium (224.58 kg ha⁻¹) were recorded under Apricot + Moong bean (T4), while minimum values were observed in sole cropping treatments (Table 2).

Soil organic carbon and soil moisture

Soil organic carbon content increased significantly under agroforestry treatments, with the highest value (0.68%) recorded under Apricot + Rajmash (T3) (Table 3). Soil moisture content was also significantly higher in agroforestry plots, with a maximum of 10.01% observed in Apricot + Moong bean (T4).

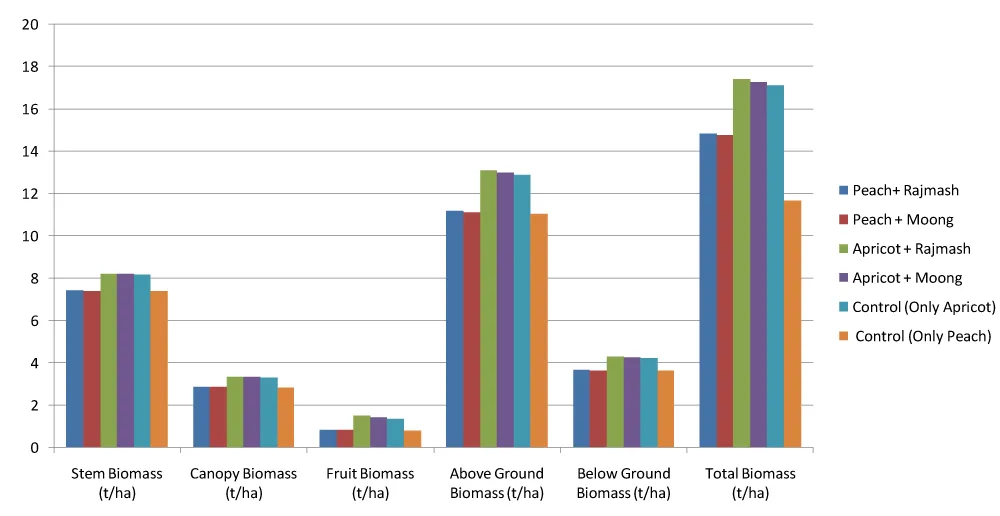

Biomass production of fruit trees

Agroforestry treatments significantly influenced stem biomass, canopy biomass, fruit biomass, above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass, and total biomass of fruit trees (Table 4)(Figure 1). The highest stem biomass (8.22 t ha⁻¹), canopy biomass (3.36 t ha⁻¹), fruit biomass (1.52 t ha⁻¹), and total tree biomass (17.42 t ha⁻¹) were recorded under Apricot + Rajmash (T3), followed closely by Apricot + Moong bean (T4). The lowest biomass values were observed under sole Peach plantations (T6).

Carbon density and carbon stock

Tree carbon density, soil carbon stock, and total ecosystem carbon pool varied significantly among treatments (Table 5). The highest tree carbon density (8.71 t ha⁻¹) and total carbon pool (52.88 t ha⁻¹) were recorded under Apricot + Rajmash (T3), whereas the lowest total carbon pool (34.13 t ha⁻¹) was observed under sole Moong bean (T7). Soil carbon stock ranged from 33.50 to 43.75 t ha⁻¹, with agroforestry treatments consistently outperforming sole cropping systems.

Discussion

Soil health improvement under agroforestry systems

The reduction in soil bulk density under agroforestry systems can be attributed to increased organic matter inputs from tree litter and root turnover, which improve soil aggregation and porosity. Similar reductions in bulk density under tree-based systems have been reported by Bargali, et al. [22] and Kumar, et al. [23] in Himalayan agroforestry systems. Lower soil pH and EC observed under agroforestry systems are likely due to organic acid production during litter decomposition and enhanced leaching of soluble salts. Comparable trends have been reported by Pandey, et al. [24] in fruit-based agroforestry systems.

Enhancement of soil nutrient status

The significant increase in available N, P, and K under agroforestry systems highlights the role of trees in nutrient cycling through litterfall, root exudation, and microbial activity. Recent studies by Tamang, et al. [25] and Dhyani, et al. [26] also reported higher soil fertility in agroforestry compared to monocropping systems.

Soil organic carbon and moisture dynamics

Higher soil organic carbon and moisture content under agroforestry systems confirm their potential in restoring degraded soils. Increased carbon inputs from perennial tree components and reduced evaporation losses due to canopy cover explain these improvements. Similar findings were reported by Nair, et al. [27], Rao, et al. [28], and Chaudhary, et al. [29].

Biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration

Greater biomass accumulation under Apricot-based agroforestry systems reflects species-specific growth characteristics and positive tree–crop interactions. Trees contribute significantly to above- and below-ground carbon pools, enhancing overall carbon sequestration. Studies by Jose, et al. [30], Yadav et al. [31], and Mandal, et al. [32] support the superior carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems over sole cropping.

Ecosystem carbon stock and climate mitigation potential

The higher total ecosystem carbon stock recorded under agroforestry treatments underscores their importance in climate change mitigation. Integration of fruit trees with annual crops offers a sustainable land-use option for degraded Himalayan landscapes, as also reported by Benbi, et al. [33], Kumar, et al. [34], and FAO [35,36].

Conclusion

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate that agroforestry systems significantly improve soil physico-chemical properties and enhance carbon sequestration compared to sole cropping systems. Tree-based intercropping practices led to reduced soil bulk density, pH, and electrical conductivity, while boosting organic carbon, available macronutrients (N, P, K), and soil moisture content. These improvements are attributed to continuous organic inputs through litterfall, root turnover, and enhanced microbial activity under diversified vegetation cover. Furthermore, agroforestry systems exhibited higher biomass and soil carbon stocks, with the combination of fruit trees and legumes (e.g., Apricot + Rajmash) showing the greatest potential for carbon accumulation. The results confirm that agroforestry serves a dual function: improving soil health and acting as an effective carbon sink. Thus, integrating fruit trees with crops is a promising climate-smart land use strategy that supports both environmental sustainability and long-term soil productivity, particularly in fragile ecosystems like the Indian Himalayas.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to convey heartfelt appreciation to the Department of Silviculture and Agroforestry, SKUAST –K for offering an excellent educational setting and improved resources that enabled us to successfully conduct research and expand understanding.

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This research does not contain any studies that include the human population or animals.

Consent to Publish: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of data and material: The data will be provided on a reasonable request, if required, and the corresponding author will provide the data.

Competing interests: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest for this submission.

Funding: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

- G.M Bhat – Main advisor of the research

- Beenish Fayaz- who conducted this research

- Vaishnu Dutt- Advisory member who helped in conducting the research

- Dr N.A Pala- Helped in data analysis

- Megna Rashid –advisory member, provides suggestions and other support during research

- Sufiya Shabir- she wrote this paper and is the corresponding author of this paper

- Chauhan SK, Mangat PS. Poplar-based agroforestry is ideal for Punjab, India. Asia-Pac Agrofor News. 2006;28:7-8.

- Dagar JC, Singh AK, Arunachalam A. Agroforestry systems in India: livelihood security & ecosystem services. Advances in Agroforestry. New Delhi: Springer; 2014. p. 400. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-81-322-1662-9

- Dhyani SK, Handa AK, Uma. Area under agroforestry in India: an assessment for present status and future perspective. Indian J Agrofor. 2013;15(1):1-11. Available from: https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/IJA/article/view/103605

- Central Agroforestry Research Institute (CAFRI). CAFRI Vision 2050. Jhansi (UP), India: CAFRI; 2015. Available from: https://cafri.res.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CAFRI__Jhansi__Vision_2050.pdf

- Nair PKR, Kumar BM, Nair VD. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2009;172:10-23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200800030

- Indian Council of Agricultural Research. Handbook of agriculture. New Delhi: Directorate of Information and Publications of Agriculture, ICAR; 2010;1617. Available from: https://icar.org.in/en/node/2811

- Subba B, Dhara PK, Panda S. Agri-horti-silvi models for sustained land use and conservation in the hill zone of West Bengal. J Hill Agric. 2017;8(1):81-86. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5958/2230-7338.2017.00021.0

- Bellow JG. Fruit-tree-based agroforestry in the Western highlands of Guatemala: an evaluation of tree-crop interactions and socio-economic characteristics [dissertation]. Florida (USA): University of Florida; 2004. Available from: https://www.coaps.fsu.edu/pub/bellow/bellow%202004.pdf

- Pandey AK, Gupta VK, Solanki KR. Productivity of neem-based agroforestry system in the semi-arid region of India. Range Manag Agrofor. 2010;31(2):144-149. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286720313_Productivity_of_neem-based_agroforestry_system_in_semi-arid_region_of_India

- Subbaiah BV, Asija GL. A rapid procedure for the estimation of available nitrogen in soils. Curr Sci. 1956;25:259-260. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=2138694

- Olsen SR, Cole CV, Watanabe IS, Dean LA. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. Washington (DC): US Department of Agriculture; 1954. Circular No. 939. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1117235

- Jackson ML. Soil chemical analysis. New Delhi: Prentice Hall of India; 1973;498. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1453838

- Piper CS. Soil and plant analysis. Bombay: Hans W.S. Publishers; 1966;464. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2430186

- Walkley A, Black IA. An examination of the digestion method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934;37:29-38. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1782155

- Brown S, Gillespie AJR, Lugo AE. Biomass estimation method for tropical forests with application to forestry inventory data. For Sci. 1989;35(4):881-902. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/35.4.881

- Bhatt BP, Toderia NP. Fuel wood characteristics of some mountain trees and shrubs. Biomass. 1992;21:233-238.

- Avery TE, Burkhart HE. Forest measurements. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2002;137-156. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3377804

- Smith DM. Maximum moisture content for determining the specific gravity of small wood samples. Madison (WI): USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory; 1954. Report No.: 2014. Available from: https://archive.org/details/CAT11137690/page/n1/mode/2up

- Singh B. Bioeconomic appraisal and carbon sequestration potential of different land use systems in the temperate north-western Himalayas [dissertation]. Solan (India): Dr YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni; 2010. Available from: https://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/items/09fdbdf4-13a0-402b-8e4c-fabac68c53cc

- Nelson DW, Sommers LE. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In: Sparks DL, editor. Methods of soil analysis. Part 3. Chemical methods. Soil Science Society of America Book Series No. 5. Madison (WI): Soil Science Society of America; 1996; 961-1010. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=2017439

- Gomez KA, Gomez AA. Statistical procedures for agricultural research. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1984. p. 680. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=2253909

- Bargali SS, Bargali K, Singh SP. Structure, composition, and biomass of agroforestry systems in the Central Himalaya, India. Agrofor Syst. 2018;92:141-153.

- Kumar BM, Nair PKR, Nair VD. Carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems. Adv Agron. 2020;163:237-307. Available from: https://library.uniteddiversity.coop/Permaculture/Agroforestry/Carbon_Sequestration_Potential_of_Agroforestry_Systems-Opportunities_and_Challenges.pdf

- Pandey DN, Gupta AK, Anderson DM. Rainwater harvesting, agroforestry, and climate resilience in the Indian Himalayas. Environ Dev. 2019;30:16-27.

- Tamang S, Sarkar BC, Dutta P. Impact of agroforestry systems on soil fertility and carbon sequestration in eastern Himalayas. Agrofor Syst. 2020;94:181-194.

- Dhyani SK, Newaj R, Sharma AR. National agroforestry policy in India: a low-hanging fruit. Curr Sci. 2022;122(2):150-156.

- Nair PKR, Nair VD, Kumar BM, Haile SG. Soil carbon sequestration in tropical agroforestry systems: a feasibility appraisal. Environ Sci Policy. 2018;85:13-22.

- Rao GG, Dhyani SK, Kumar S. Agroforestry for sustainable soil and water management under a changing climate. Indian J Agrofor. 2021;23(1):1-12.

- Chaudhary S, Dagar JC, Gupta G. Agroforestry systems for restoring soil health and enhancing ecosystem services under climate change. Agrofor Syst. 2023;97:215-231.

- Jose S, Bardhan S, Udawatta RP. Agroforestry for biomass production and carbon sequestration: an overview. Agrofor Syst. 2019;93:1045-1061. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257510488_Agroforestry_for_biomass_production_and_carbon_sequestration_An_overview

- Yadav RS, Yadav BL, Meena RH. Carbon sequestration potential of agri-horti systems in semi-arid regions of India. J Environ Manage. 2020;260:110144.

- Mandal D, Dhyani SK, Meena VS. Agroforestry systems for carbon sequestration and climate resilience in India. Environ Sustain. 2022;5:411-424.

- Benbi DK, Brar K, Toor AS, Singh P. Total and labile pools of soil organic carbon in cultivated and undisturbed soils of northern India. Geoderma. 2017;295:76-82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.09.002

- Kumar S, Meena RS, Lal R, Yadav GS. Soil organic carbon dynamics in agroforestry systems: a review. J Clean Prod. 2021;316:128318. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-014-0212-y

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Agroforestry for sustainable agriculture and food systems. Rome: FAO; 2022. Available from: https://www.fao.org/agroforestry/en

- Tomich TP, de Foresta H, Dennis R. Carbon offsets for conservation and development in Indonesia. Am J Altern Agric. 2002;17:125-137.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley