Annals of Environmental Science and Toxicology

Iodine Enrichment and Climate Change - How Iodine Shaped our World

1UCD School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

2Ryan Institute’s Centre for Climate & Air Pollution Studies, School of Physics, University of Galway,Galway, Ireland

Author and article information

Cite this as

Smyth PPA, et al. Iodine Enrichment and Climate Change - How Iodine Shaped our World. Ann Environ Sci Toxicol. 2025; 9(1): 053-057. Available from: 10.17352/aest.000091

Copyright License

© 2025 Smyth PPA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Data arising from the early history of the Earth demonstrates how iodine contributed to the development of life and how iodine deficiency may have led to the disappearance of our Neanderthal predecessors. In modern times, problems such as the incidence of endemic cretinism (severe hypothyroidism) and goitre (thyroid enlargement) associated with iodine deficiency were recognised and continue to be addressed with varying success by dietary iodine supplementation. Volatile iodine compounds released from the marine environment make an important contribution to diminishing pollutant ozone, with increases in global volatile iodine influencing climate change. The prospect that current pollutants induced global warming may significantly extend the present interglacial period suggests that increased global iodine may persist. The consequences for thyroidal health and human development of a new iodine-replete earth are unknown. It appears that iodine, in addition to helping shape our world, continues to have the potential to significantly influence all our futures.

The current crisis brought about by climate change-induced global warming has manifested itself in melting of the polar ice caps, rising sea levels, climatic disruption, mass migration, and food shortages, to mention but a few [1]. A lesser-known consequence of climate change arising from ocean expansion and manmade pollution is an increase in atmospheric iodine [2]. Evidence has been provided that in prehistoric times, the stability and abundance of the ozone (O3) layer, particularly in the lower atmosphere (troposphere), was shaped by marine iodine emissions, thereby controlling damaging solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) effects on the development of complex cellular life, particularly on land [3]. They further described evidence for the marine iodine reservoirs in the Proterozoic eon, which lasted from 2.5 billion to 538.8 million years ago, was at least five times higher than today, and that the decline in marine iodine over the millennia reflected the evolution of an iodine cycle with bioavailable global iodine levels varying with atmospheric change.

Iodine is essential for thyroid hormone synthesis, bioavailability and dietary intake of iodine is of fundamental importance in human biology and plays a central role in human growth and development [4-8], both as an essential dietary mineral and as a proxy for thyroid hormones (TH). The recent suggestion that climate change may impact global iodine status [9,10] has additional potential implications for iodine and TH influences that might arise in an iodine-replete world.

Iodine and the marine environment

The marine environment provides a major source of iodine. Although the concentration of iodine in seawater is relatively low (approx. 58 μg/L), the great mass of the oceans makes it the major source of iodine on the planet. Iodine in seawater is mainly present as I− and IO3 -, with I− predominating in surface waters while IO3 - forms the greatest proportion in deep water [11]. The concentration of I− in surface water also depends on phytoplankton primary (biotic) productivity, ocean circulation and vertical mixing, pH, and oxygen levels [2,3,12]. Geography and seasonal factors play a large part in higher concentrations of I− being present in warmer tropical waters or in subtropical gyres (rotating ocean currents) [2,3,12].

Iodine and the atmosphere

Among the changes brought about by global warming-induced rising sea levels is an increase in atmospheric volatile iodine compounds such as iodine (I2) or hypoiodic acid (HOI) [2,3]. This increase in atmospheric iodine can be attributed to man-made pollution arising from greenhouse gases produced in the current industrial era of the Anthropocene (1760 to date) [2].

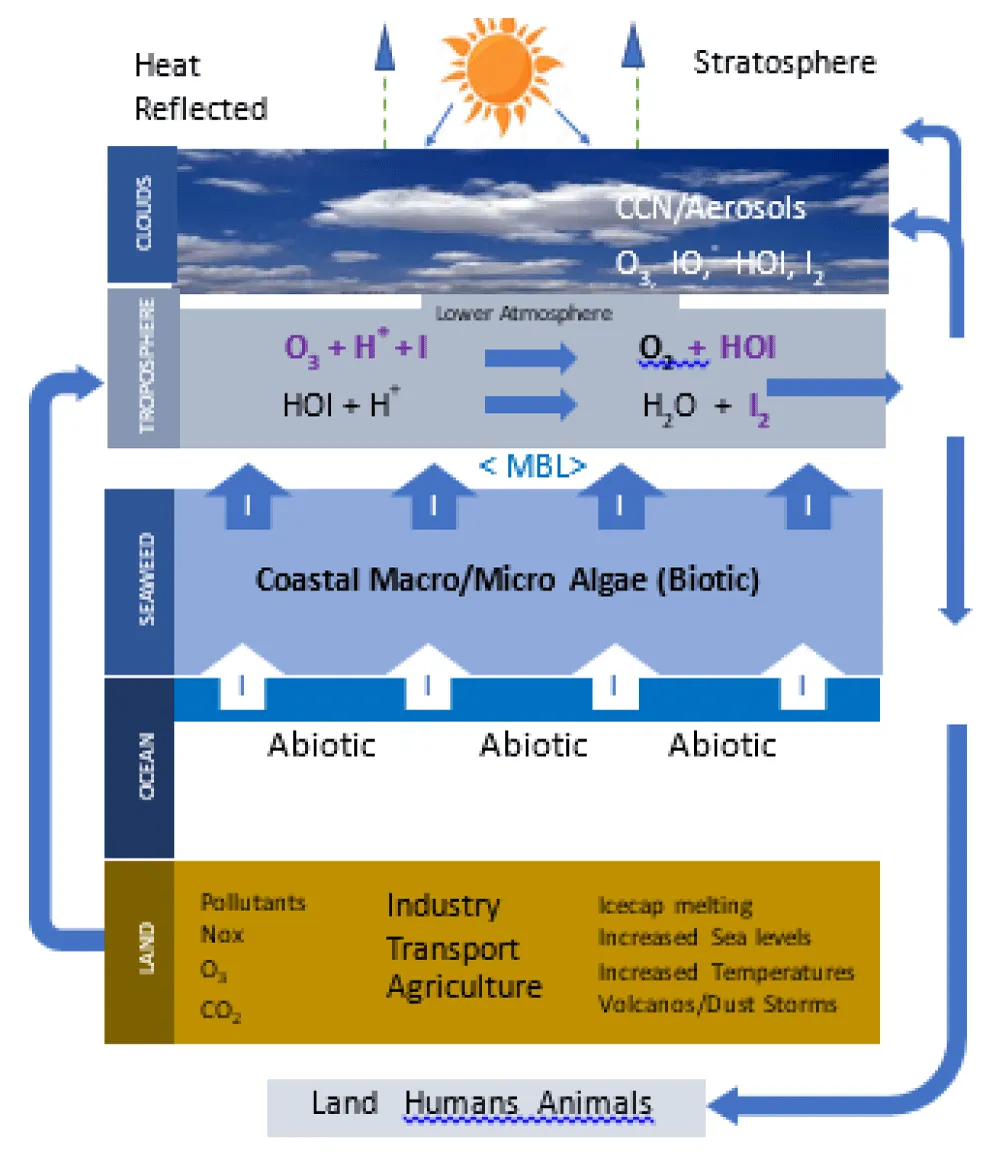

Figure 1 shows in diagrammatic form the interactions between various iodine species and atmospheric gases, both natural and anthropogenic, involved in global warming. I- present at the seawater surface reacts with tropospheric O3 - to form gaseous I2 and HOI, thus reducing potentially harmful O3 [2,10]. Atmospheric iodine has been shown drive marine particle formation, leading to new aerosol particles that ultimately produce cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), from which cloud droplets can form, leading to cloud formation [13]. Reduction of tropospheric O3 and generation of volatile I2/HOI with cloud formation and brightening reflect more sunlight into space. Such cloud formation in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) by reflecting incoming solar heat leads to negative radiative forcing contributing to global cooling.

In the case of seaweed-abundant coastal It has been estimated that marine algae can supplement seawater I2 release [2,10,14]. The reaction of O3 with I- accomplishes two results. It is the major source of volatile iodine at the sea surface and, in turn, reduces potentially harmful O3 in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) up to 14 km above sea level [2,3). It has been estimated that iodine causes a reduction of tropospheric O3 of approximately 15% [2]. This obviously varies with season and region sampled. Higher surface water concentrations of I- are observed in warmer low latitude climates with greater I- and iodine release in summer than in winter [2,12]. Current understanding of the iodine cycle has been derived from specific study regions, and uncertainty remains on whether these findings can be applied on a global scale [2,12].

Much of the evidence for increases in iodine supply was based on alterations observed from the last 11,700 years (Holocene) to the current Anthropocene [9,15,16]. These authors demonstrated a recent 3-fold increase in ice core iodine values reflecting atmospheric iodine deposition sampled in Greenland and in Alpine ice cores. In addition, thinning of the ice sheet allowed sunlight to promote iodine release from phytoplankton, which more readily diffused through the thinner ice [2,17]. Ozone and other tropospheric air pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), act to provide a barrier to heat escape from the Earth, causing cloud brightening and ultimately higher cloud reflectance, resulting in global warming. In contrast to global warming, which involves loss of ice-bound iodine, glacial periods sequester large amounts of water in ice fields, diminishing bioavailable iodine [2,9]. Melting of the icefields would cause this iodine to be released, with global warming generating the larger atmospheric iodine observed with retreat of ice fields in spring and summer [2]. When the ice cap refreezes in winter, the thinner ice is also more permeable to iodine formation and release [9,17,18]. Another contributor to global iodine is its presence in dust carried into the atmosphere from deserts or volcanic eruptions [19]. It has been found that O3 within dust layers has been diminished by 75%, with iodine levels highest where O3 is lowest. The lowering of ocean pH because of increases in the greenhouse gas CO2, which, when dissolved in seawater, forms H2CO3, also contributes to gaseous iodine release [20], as acid pH favours the reduced I− over the oxidised IO3− speciation. The consequence of such increases in global iodine levels, both atmospheric and deposited in rain, remains unknown.

Of course, the authors understand that iodine concentrations may be the least of our worries if global warming brings about melting of the polar ice caps, rising sea levels, climatic disruption, mass migration, and food shortages, to mention but a few [1]. An additional threat particularly relevant to North America and Europe is the tipping point for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which, if reached, could reverse ocean currents, resulting in extreme weather events impacting the arrival of another glacial period [21,22]. Human intervention may prevent the worst of these happenings, but is unlikely to prevent a long-term increase in global iodine.

Iodine and evolution

The evolutionary roots of iodine, starting with marine algae (seaweeds), provide a source of atmospheric iodine serving as a dietary source for mammals, an antimicrobial agent, and the earliest inorganic antioxidant in the marine environment capable of detoxifying reactive oxygen species and ozone [2,4,18,23]. Primitive cells in marine algae can concentrate iodide, which, in more developed organs, is able to combine with tyrosine and incorporate the accumulated iodide into the iodothyronine thyroxine (T4), which could be deiodinated by peroxidases to the biologically active triiodothyronine (T3). The ability in primitive marine systems, such as algae, to concentrate iodide may, when life emerged from the sea, have formed the basis for the food chain with nutritional changes suggested as leading to an increased iodine requirement [24].

Iodine deficiency

A role for Iodine deficiency and its consequences in terms of reduced thyroid hormone production has resulted in a disease spectrum ranging from mild thyroid hypofunction to the profound symptoms found in overt hypothyroidism with impaired physical and mental development of cretinism [4,25]. The introduction of iodine prophylactic programmes such as iodisation of table salt, Universal Salt Iodisation (USI), or use of iodised salt in bread baking has been very successful in correcting iodine deficiency, but not all benefit equally from such programmes, particularly pregnant mothers or those on specialty diets such as vegans [25,26]. Correction of iodine deficiency has its own problems, carrying the risk of an increase in the prevalence of toxic nodular goitre and hyperthyroidism in previously iodine-deficient populations [25]. Although cretinism has largely disappeared from Europe, despite recent improvements in Universal Salt Iodisation (USI), iodine deficiency disorders (IDD) persist in large areas of the world and iodine deficiency remains the principal cause of preventable mental retardation [26].

Iodine and neanderthals

One of the unsolved evolutionary mysteries concerns the disappearance of Neanderthals some 39,000 years ago. Although it appears that Neanderthal disappearance occurred at different times in different regions, the Neanderthals showed a considerable overlap with Anatomically Modern Humans (AMH), coexisting for a period of between 2600 and 5400 years [27] and most probably interacting, thereby sharing genes [28,29]. The current majority view is that the extinction of Neanderthals, coupled with the survival of contemporary coexisting AMH, could be attributed to the inability of Neanderthals to withstand competition [27,29]. A hypothesis implicating iodine deficiency in Neanderthal extinction has been advanced [8], as has the finding in Neanderthals of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the deiodinase DIO2 gene preventing the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to physiologically active triiodothyronine (T3), which would be critical in iodine-deficient individuals surviving in an extremely cold climate [30]. Whatever the cause, the population of AMH survived while the Neanderthals disappeared.

Development of an iodine enriched atmosphere

In contrast to global warming, which involves loss of ice-bound iodine, glacial periods would, by sequestering large amounts of water in ice fields, diminish bioavailable iodine [15,16]. Melting of the icefields will result in this iodine being released with the retreat of ice fields in spring and summer [15,16]. The suggestion that global iodine levels may in the near future reach their highest level for the past 127,000 years, that is, the Eemian interglacial period about 100,000 years ago, which preceded our current Holocene or Anthropocene, should at least prompt us to explore what effects such a dramatic change might present, not least iodine induced, for future human evolution [10,16].

The difference between the Holocene and earlier epochs is the effect of human activity, specifically industrial pollution, which reflects the influence of recent humankind on the Earth in producing greenhouse gases, particularly since the beginning of the Industrial Age. c 1760, now referred to as the Anthropocene. The effects of this activity have greatly increased since the 1950s, leading to the increases in terrestrial iodine recorded and projected [9,15,16]. Recent interglacial periods have lasted for approximately 10,000 years, but it has been suggested that the climate change arising from man-made global warming may extend the current period for up to 50,000 – 100,000 years with consequent implications for increased global iodine [31,32]. Of course, climate change and global warming do not exclusively depend on manmade pollution. Variations in the Earth’s orbit, which determine the amount of sunlight warming the Earth (Insolation) over the millennia, continue to exert a major role [33]. If the pollutant emissions reach the highest predicted level, glaciation would be delayed for up to 0.5 million years. Human fossil fuel use may therefore create a super-interglacial period that has overridden the insolation effect of orbital forcing on Earth’s climate [33].

Gaseous iodine released in the atmosphere can be returned to Earth via rainfall or possibly imbibed by humans through respiration [14]. Although iodine deposited in rainfall is obviously dependent on local climatic conditions and atmospheric iodine concentration, attempts to calculate human iodine intake by respiration have suggested a possible marginal increase in human populations [10,14]. The wider question of fresh air contributing to human nutrition (aeronutrients) has recently been explored [34]. In assessing the possible role of iodine inhalation, subjects studied were female schoolchildren (aged< 15 years) attending schools in areas of both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland [10]. Higher intakes, such as those recorded by populations living adjacent to a seaweed-abundant area, might indicate levels that could be achieved during a prolonged period of global warming. Highest levels over the seaweed hotspot were equivalent to a supplementary intake of 46-81 µg /Day (WHO recommended daily adult intake 120 µg [10,14]. The iodine levels recorded over a seaweed bed were achieved at different times (day and night), distances from the seaweed bed, and wind speeds [10]. The highest values were observed over the seaweed beds at nighttime, with lower photolytic destruction, while lower values occurred downwind in calm daylight. Of course, applying these values to other non-seaweed-rich areas must remain highly speculative. The short-term increases in atmospheric iodine predicted by local studies [10] and near-term anthropogenic effects [15] must be distinguished from the longer-term climatic changes that may result from isolation and possible extension of interglacial periods. It is unlikely that such a limited increase in iodine intake would significantly alter individual thyroid function in the short term, but an effect over a prolonged period cannot be excluded.

Possible thyroidal and extrathyroidal effects arising from climate change

A process dictated by thyroid hormones has been suggested to exert allosteric control of energy balance, overriding homeostatic controls at times of stress [35]. Thus, brain function takes precedence over lower-priority functions such as growth, reproduction, and fat deposition. Type 2 allostasis is believed to occur when the body encounters a change in environmental conditions and predicts if a shift in energy demands can be met by utilising existing energy stores and increasing caloric intake [35]. Whether a prolonged increase in global iodine would provoke a change in thyroid hormone-mediated energy balance, as indicated by type 2 allostasis, is a matter of conjecture. In view of the lower cognitive abilities recorded in even marginally iodine-deficient children [36], could an iodine-replete population presage a potential increase in worldwide human potential? The Effects of increased iodine bioavailability would obviously have the greatest consequences in populations whose current dietary iodine intake is either deficient or below optimum. A gradual increase in atmospheric iodine would, over time, obviate the need for iodine prophylaxis programmes such as Universal Salt Iodisation (USI) [26]. It is, of course, not possible to apply the potential increases in atmospheric iodine observed over seaweed masses to non-seaweed-rich global areas [14]. However, the persistent future high global iodine predicted could result in iodine increments comparable to the modest increases observed over seaweed-abundant regions. Such increments would be unlikely to achieve levels that could result in iodine excess [10].

Changes or the absence of change in the presentation of thyroid disease have been reported following programmes of salt iodisation, but these have been relatively short-term and scarcely apply over the millennia required for evolutionary change. Undoubtedly, the human thyroid can adapt to different iodine intakes, as demonstrated by the Japanese experience, where daily dietary iodine intakes of approximately 1 mg [37] orders of magnitude greater than Western intake can be readily tolerated.

Conclusion

The current period of global warming arising from climate change has the potential to greatly increase global iodine. If, as projected, the results of manmade global warming persist, resulting in an extended interglacial period, the increase in iodine will be prolonged. The result of competition between anthropogenically induced climate change and the onset of the next glacial period is obviously impossible to predict, but is unlikely to significantly alter global iodine status in the current millennium. Other volatile compounds released into the atmosphere may also affect human health [34] but are unlikely to have the fundamental effects of iodine/TH action on human development. It may be that current efforts to reduce atmospheric pollution will reduce the damaging effects of global warming, including the release of volatile iodine compounds. However, it is unlikely that such efforts, even if partly successful, will in the short term alter the atmospheric iodine burden. In the event of higher iodine levels persisting, which itself is highly speculative, it is tempting to consider what effect an iodine level at its highest in the last 127,000 years might produce [16]

Any potential iodine effects would obviously be diluted by the enormous, perhaps existential, consequences of climate change. Our predecessors over the recent Holocene epoch, unlike the unfortunate Neanderthals from an earlier epoch, have survived and prospered despite many climatic changes, which must give us, an iodine replete homo sapiens, or other possible hominid successors, increased hope for a benign if uncertain evolutionary future. Thus, the possibility exists that the deleterious effects of climate change may have a paradoxically beneficial influence on human development.

The authors are grateful to Christopher Murphy, B.Des, for design advice.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2023: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Core Writing Team, Lee H, Romero J, editors. Geneva (Switzerland): IPCC. 2023;184. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf

- Carpenter L, Chance RJ, Sherwen T, Adams TJ, Ball SM, Evans MJ, et al. Marine iodine emissions in a changing world. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 2021;477:20200824. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspa.2020.0824

- Liu J, Hardisty D, Kasting J, Fakhraee M, Planavsky N. Evolution of the iodine cycle and the late stabilization of the Earth’s ozone layer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2025;122. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2412898121

- Yun AJ, Lee PY, Bazar KA, Daniel SM, Doux JD. The incorporation of iodine in thyroid hormone may stem from its role as a prehistoric signal of ecologic opportunity: an evolutionary perspective and implications for modern diseases. Medical Hypotheses. 2005;65(4):804–810. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306987705001144

- Venturi S. Evolutionary significance of iodine. Current Chemical Biology. 2011;5:155–162. Available from: https://www.eurekaselect.com/article/23863

- Mourouzis I, Lavecchia AM, Xinaris C. Thyroid hormone signalling: from the dawn of life to the bedside. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2020;88:88–103. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00239-019-09908-1

- Mantzouratou P, Lavecchia AM, Xinaris C. Thyroid hormone signalling in human evolution and disease: a novel hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(1):43. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/1/43

- Dobson JE. The iodine factor in health and evolution. Geographical Review. 1998;88:3–28. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1931-0846.1998.tb00093.x

- Cuevas CA, Maffezzoli N, Corella JP, Spolaor A, Vallelonga P, Kjær HA, et al. Rapid increase in atmospheric iodine levels in the North Atlantic since the mid-20th century. Nature Communications. 2018;9:1452. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-03756-1

- Smyth PP, O'Dowd CD. Climate changes affecting global iodine status. European Thyroid Journal. 2024;13(2):e230200. Available from: https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/13/2/ETJ-23-0200.xml

- Truesdale VW, Bale AJ, Woodward EMS. The meridional distribution of dissolved iodine in near-surface waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Progress in Oceanography. 2000;45:387–400. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079661100000094

- Wadley MR, Stevens DP, Jickells TD, Hughes C, Chance R, Hepach H, et al. A global model for iodine speciation in the upper ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2020;34:e2019GB006467. Available from: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/essoar.10502078.2

- O'Dowd CD, Jimenez JL, Bahreini R, Flagan RC, Seinfeld JH, Hameri K, et al. Marine aerosol formation from biogenic iodine emissions. Nature. 2002;417:632–636. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature00775

- Smyth PPA, Burns R, Huang RJ, Hoffman T, Mullan K, Graham U, et al. Does iodine gas released from seaweed contribute to dietary iodine intake? Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2011;33:389–397. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10653-011-9384-4

- Legrand M, McConnell JR, Preunkert S, Arienzo M, Chellman N, Gleason K, et al. Alpine ice evidence of a three-fold increase in atmospheric iodine deposition since 1950 in Europe due to increasing oceanic emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2018;115:12136–12141. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1809867115

- Corella JP, Maffezzoli N, Spolaor A, Vallelonga P, Cuevas CA, Scoto F, et al. Climate changes modulated the history of Arctic iodine during the last glacial cycle. Nature Communications. 2022;13:88. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-27642-5

- Benavent N, Mahajan AS, Li Q, Cuevas CA, Schmale J, Angot H, et al. Substantial contribution of iodine to Arctic ozone destruction. Nature Geoscience. 2022;15:770–773. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-022-01018-w

- Kupper FC, Carpenter LJ, McFiggans GB, Feiters MC. Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:6954–6958. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0709959105

- Koenig TK, Volkamer R, Apel EC, Bresch JF, Cuevas CA, Dix B, et al. Ozone depletion due to dust release of iodine in the free troposphere. Science Advances. 2021;7:eabj6544. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abj6544

- Baker AR, Yodle C. Measurement report: indirect evidence for the controlling influence of acidity on the speciation of iodine in Atlantic aerosols. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2021;21:13067–13076. Available from: https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/21/13067/2021/

- Ramsdorf S. Is the Atlantic overturning circulation approaching a tipping point? Oceanography. 2024;37(3):16–29. Available from: https://tos.org/oceanography/article/is-the-atlantic-overturning-circulation-approaching-a-tipping-point

- Hansen JE, Kharecha P, Sato M, Tselioudis G, Kelle J, Bauer SE, et al. Global warming has accelerated: are the United Nations and the public well-informed? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 2025;67(1):6–44. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00139157.2025.2434494

- Crockford SJ. Evolutionary roots of iodine and thyroid hormones in cell–cell signaling. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2009 Aug;49(2):155–166. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/icb/article/49/2/155/652433

- Kopp W. Nutrition, evolution and thyroid hormone levels: a link to iodine deficiency disorders? Medical Hypotheses. 2004;62:871–875. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306987704000654

- Zimmermann MB, Boelaert K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2015 Apr;3(4):286–295. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213858714702256

- Zimmermann MB. The remarkable impact of iodisation programmes on global public health. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2023;82(2):113–119. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-nutrition-society/article/remarkable-impact-of-iodisation-programmes-on-global-public-health/

- Higham T, Douka K, Wood R, Ramsey CB, Brock F, Basell L, et al. The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance. Nature. 2014;512:306–309. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13621

- Timmermann A. Quantifying the potential causes of Neanderthal extinction: abrupt climate change versus competition and interbreeding. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2020;238:106331. Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2020QSRv..23806331T/abstract

- Banks WE, d’Errico F, Peterson AT, Kageyama M, Sima A, Sanchez Goni MF, et al. Neanderthal extinction by competitive exclusion. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3972. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003972

- Ricci C, Kakularam KR, Marzocchi C, Capecchi G, Riolo G, Boschin F, et al. Thr92Ala polymorphism in the type 2 deiodinase gene: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2020;43:1749–1757. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40618-020-01287-5

- Berger A, Loutre MF. An exceptionally long interglacial ahead? Science. 2002;297:1287–1288. Available from: https://svalgaard.leif.org/EOS/Berger-and-Loutre-2002.pdf

- Ganopolski A, Winkelmann R, Schellnhuber HJ. Critical insolation–CO2 relation for diagnosing past and future glacial inception. Nature. 2016;529:200–203. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature16494

- Maslin MT, Fan Q, Yao Y. Tying celestial mechanics to Earth’s ice ages. Physics Today. 2020;73(5):48–53. Available from: https://physicstoday.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/PT.3.4474

- Fayet-Moore F, Robinson SR. A breath of fresh air: perspectives on inhaled nutrients and bacteria to improve human health. Advances in Nutrition. 2024;15(12):100333. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2161831324003286

- Levy SB, Bribiescas RB. Hierarchies in the energy budget: thyroid hormone and the evolution of human life history patterns. Evolutionary Anthropology. 2023;32:275–292. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/evan.22000

- Bath SC, Rayman MP. A review of the iodine status of UK pregnant women and its implications for the offspring. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2015;37(4):619–629. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10653-015-9682-3

- Nagataki S. The average of dietary iodine intake due to the ingestion of seaweeds is 1.2 mg/day in Japan. Thyroid. 2008;18:667–668. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2007.0379

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley