Anthropogenic Interference on the Ecosystem of Pangolin in Deng-Deng National Park, Eastern Region, Cameroon

1Department of Forestry and Wildlife, University of Buea, P.O. Box, Buea, Cameroon

2Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Buea, P.O. Box, Buea, Cameroon

3Department of Environmental Science, University of Buea, P.O. Box, Buea, Cameroon

Author and article information

Cite this as

Maurice ME, Ayamba AJ, Nestor FT, Ewange MB. Anthropogenic Interference on the Ecosystem of Pangolin in Deng-Deng National Park, Eastern Region, Cameroon. Glob J Ecol. 2025; 10(2): 031-039. Available from: 10.17352/gje.000113

Copyright License

© 2025 Maurice ME, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

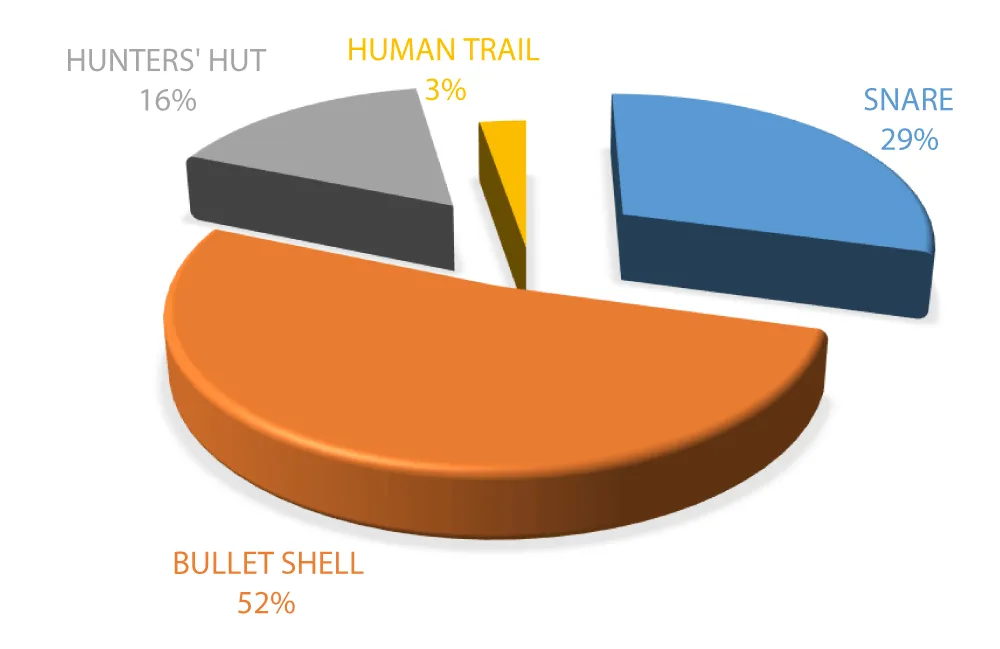

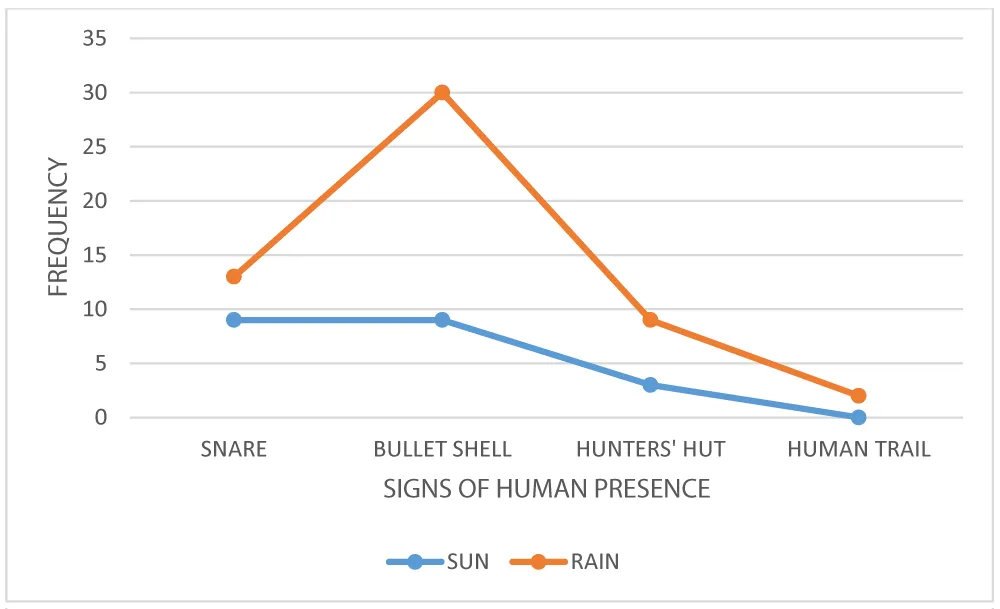

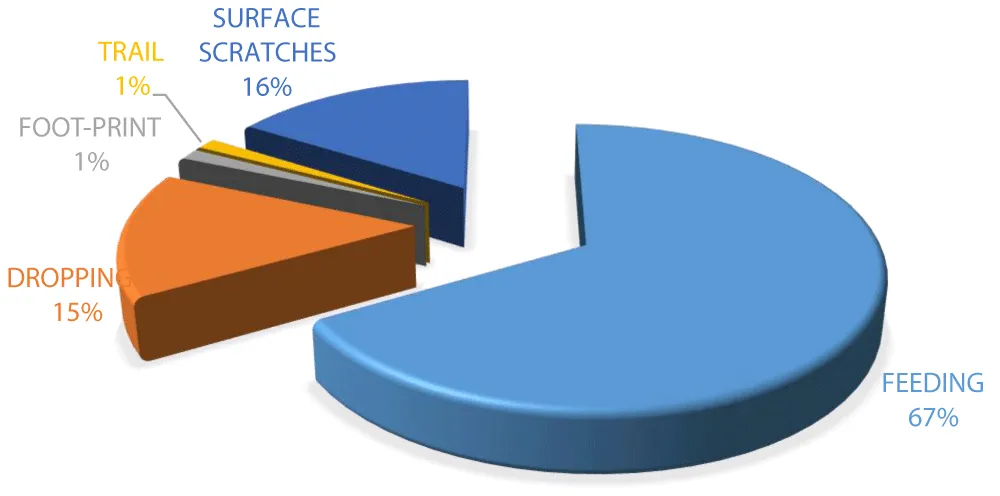

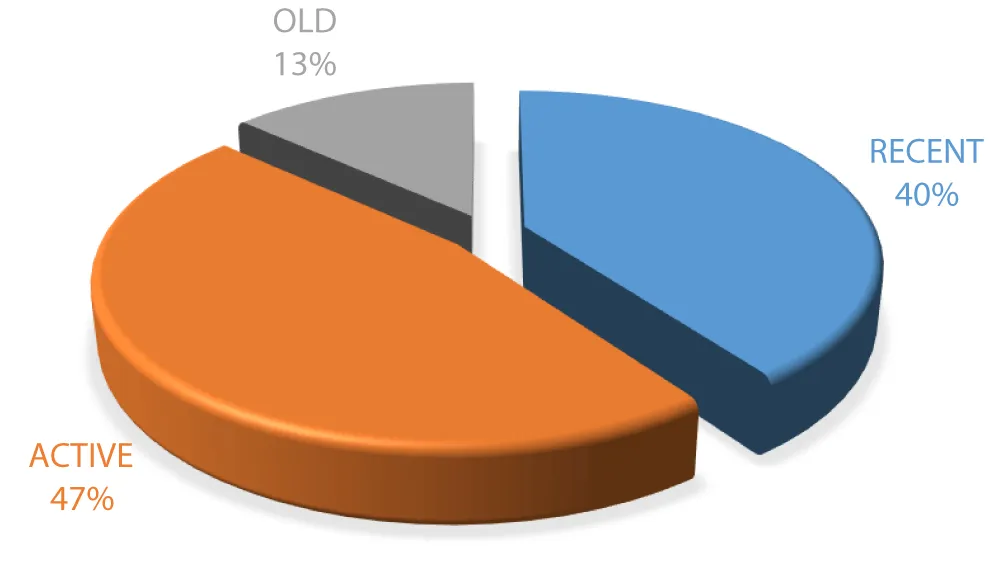

Habitat degradation and fragmentation, driven by deforestation and agricultural expansion, have resulted in the loss of suitable habitats for pangolins. Additionally, illegal hunting and trade, fueled by the demand for pangolin scales and meat, have further exacerbated population declines. The research focused on assessing the impacts of human interference on pangolins and their habitats, highlighting the need for effective conservation measures to mitigate these threats. However, the study utilized a combination of data collection methods, such as field surveys and interviews, to investigate the extent and consequences of human interference in the pangolin environment in Deng Deng-Deng National Park. The presence of human activity in the pangolin ecosystem showed a significance on forest vegetation type X2 = 18.806, df = 9, p < 0.05, forest vegetation canopy X2 = 10.528, df = 6, p < 0.05, and forest undergrowth vegetation X2 = 6.877, df = 6, p < 0.05, respectively. Empty bullet shells 52% and snares 29% recorded the highest significance of human activity, while hunters’ hut 16% and hunting human trails, 3% recorded the least, respectively. Pangolins are highly valued for their scales and meat in certain cultures, leading to illegal wildlife trade. Forest vegetation visibility recorded a significance on human signs, X2 = 3.162, df = 6, p < 0.05. The forest vegetation landscape and human signs in the pangolin environment showed a significant association as well, X2 = 8.972, df = 6, p < 0.05. More so, human interference, such as poaching, trails, and infrastructure development in pangolin environments, fragments forest landscapes and disrupts pangolin movement. Additionally, forest canopy and landscape recorded a significant X2 = 5.434 df = 4 p < 0.05. The heterogeneity of the forest landscape, which refers to the variety and spatial arrangement of different habitat types, influences the diversity and structure of the forest vegetation canopy. Furthermore, the atmospheric conditions revealed a positive association with human signs in the pangolin ecosystem, r = 0.108, p < 0.05. Also, feeding 67%, earth-surface scratches 16%, and droppings 15% recorded the highest pangolin signs, while pangolin footprints 1% and trails 1% recorded the least, respectively. Illegal hunting and trade were identified as significant factors contributing to the decline of pangolin populations. The unsustainable harvest of pangolins has led to population declines and imbalances within the park's ecosystem. The study highlights the detrimental impact of human interference on pangolin populations and their habitats within Deng Deng-Deng National Park. Also, findings emphasize the urgent need for effective conservation measures to mitigate habitat degradation, address illegal hunting and trade, and engage local communities in pangolin conservation efforts. By implementing these measures, there is a greater chance of preserving the pangolin environment and ensuring the long-term survival of these unique and endangered creatures within the park.

Introduction

Pangolins are placental mammals belonging to the order Pholidota and comprise eight species geographically restricted to the African and Asian continents [1]. Four species occur in Asia (Chinese pangolin, Indian pangolin, Philippines pangolin, and Sunda pangolin), and four other species range in Africa (giant pangolin, Temminck’s ground pangolin, black- bellied pangolin, and white-bellied pangolin). They are edentates with an elongate tongue and represent the only mammalian group with a body covered by scales. All pangolin species excavate burrows, to varying extents, and for shelter, except the black-bellied pangolin. All the species prey mainly on ants and termites [2-4] and occur within a diversity of habitats, ranging from primary to semi-degraded forests [5,6]. The international demand for pangolin scales and meat, driven by traditional medicine practices and culinary preferences, has led to a surge in poaching activities. The illegal wildlife trade network has infiltrated the Deng Deng National Park, resulting in the unsustainable harvest of pangolins and contributing to population declines. The wildlife trade is worth billions of dollars annually and affects mostly mammals [7]. Pangolins are the most traded mammals in the world, even during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic [8], and this raised a worldwide concern over the taxonomic group.

Several tons of pangolins have been harvested from their natural habitats to feed legally and illegally an international trade since the turn of the 20th century, with unequal impacts following species and continents [9]. Because the Asian pangolins have been poached to near extinction during the 20th century, the route of trafficking changed since the turn of the 21st century and an escalating growth in the illegal international rade of African pangolins took place, now targeting mainly white-bellied and giant pangolins from Africa, for their scales in particular [10-13]. Recent estimates revealed that around 900,000 African pangolins were illegally traded over the last two decades [9]. An assessment of the illegal trade chain estimated between 0.2 and 0.4 million, the number of pangolins annually harvested in Central Africa, with increasing trends over time [14]. This intercontinental trade has been confirmed using the CITES database [10,14,15], surveys in the bushmeat and traditional medicine markets [12,16,17,], but also through DNA-profiling of specimens seized in Asia in particular [11,13]. Some studies clearly established a connection between the Gulf of Guinea and Asia [12,16,17].

Endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species [18,19], the white-bellied and giant pangolins are respectively classified as Endangered and Critically Endangered on the Red List for Benin [20]. They are threatened by local trade in bushmeat and traditional medicine markets [21], and more recently by international trafficking [12,21]. The LEK-based survey suggested declining trends in occupancy area for both species. The white-bellied pangolin underwent a contraction of one-third of its occurrence range, and the giant pangolin experienced a quasi-total extirpation with 93% of its occurrence range lost over the last two decades [22]. Habitat degradation and overexploitation were the major drivers of population decline according to local hunters [22]. The two species are currently distributed in a human-dominated landscape within patchily distributed habitats [22], and this spatial configuration certainly has an influence on the persistence of the populations of many mammals [23-26].

Anthropogenic interference in the pangolin environment in Deng deng-deng national park poses significant threats to the survival of these remarkable creatures. This study seeks to shed light on the extent and consequences of anthropogenic activity, such as illegal hunting of pangolins, providing valuable information for the development of effective conservation measures. By understanding and addressing these challenges, it is possible to ensure the long-term viability of pangolin populations and preserve the ecological integrity of Deng Deng National Park. However, understanding anthropogenic interference pangolin environment is of utmost importance for the conservation and management of this endangered species.

Materials and methods

Description of study area

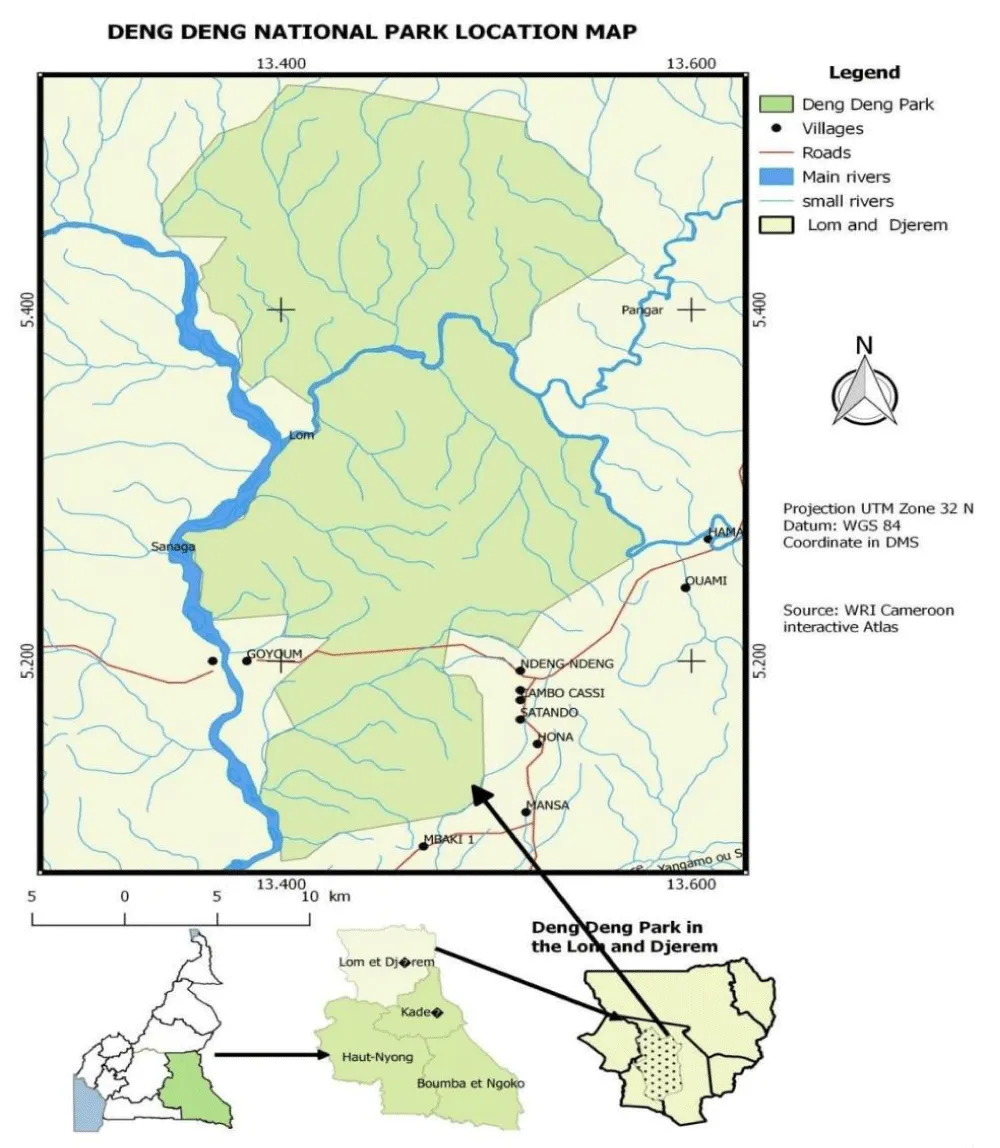

The Deng-deng national park is located in the East Region of Cameroon, precisely in Lom-et-Djerem division (Figure 1). The park covers an area of about 523 km2 and lies between latitude 13° 23 to 13° 34 East and longitude 05° 5 to 05° 25 North, in the North-Eastern part of the lower Guinean forest [27]. The national park area features a typical equatorial and humid climate [28] defined by the rainfall regime in this area. Seasonal pattern in the park area is characterized by distinct but unequal dry and wet season periods. Heavy wet season starts from August to November, a light wet season from April to June, a long dry season from December to March and a short dry season from July to mid-August. With a mean annual temperature of 23 °C, annual minimum and maximum temperatures within the park area ranged from 15° C and 31° C [29]. More so, the national park is known for its rich biodiversity and serves as an important habitat for numerous plant and animal species. The park is part of the Congo Basin forest ecosystem, which is recognized as one of the world's most significant biodiversity hotspots. It is home to a diverse range of flora and fauna, including many endemic and endangered species. It is primarily covered by tropical rainforest, characterized by tall trees, dense vegetation, and a variety of plant species. The forest canopy is often thick, allowing limited sunlight to penetrate the forest floor. The vegetation includes towering hardwood trees, lianas, epiphytes, and various understory plants. More so, it provides habitat for a number of mammal species, including elephants, chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys (such as colobus monkeys and guenons), duikers, forest buffalo, pangolins, and many other wildlife species. The park is also home to a wide range of bird species, reptiles, amphibians, and insects.

Research data collection and analysis

Investigating the interference of human activity in the pangolin environment within Deng-Deng National Park, a comprehensive data collection method was employed. Field surveys were conducted to assess the current status of pangolin habitats and gather data on pangolin ecology. The research team gathered reliable and relevant information regarding human activity significance, like illegal hunting, the presence of pangolin signs, and some ecological parameters, in order to assess the extent and consequences of these activities on pangolin welfare. Interviews with local communities, park rangers, and stakeholders were conducted to gather more information on human activities and their impact on pangolins. Interviews also provided insights into community perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge regarding pangolin conservation. More so, camera trapping was utilized as a non-invasive method to monitor pangolin populations and detect illegal activities within the park. Motion-activated cameras were strategically placed in areas of suspected pangolin habitat and potential poaching hotspots. The cameras captured images of pangolins and other wildlife species, providing valuable data on their presence, behavior, and potential threats. Quantitative data collected through field surveys, camera trapping, and questionnaires were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. Descriptive statistics, such as percentage frequencies, as well as inferential statistics, were calculated to summarize the data.

Results

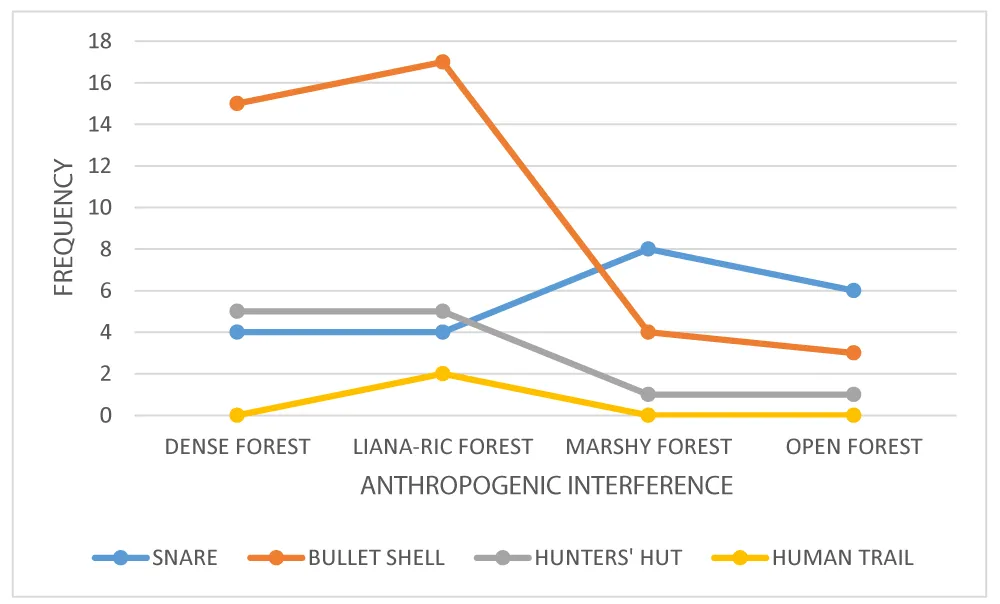

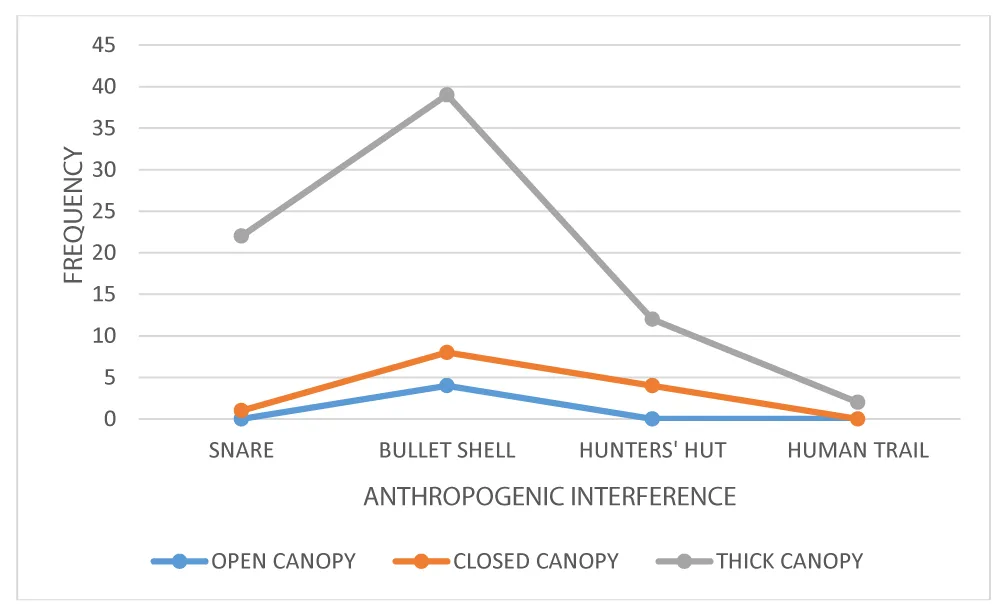

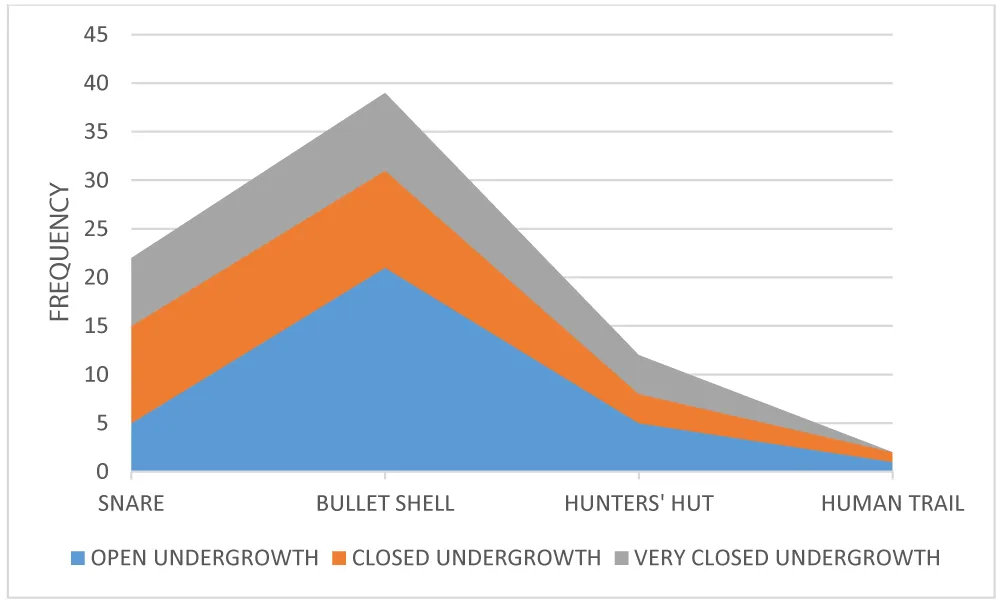

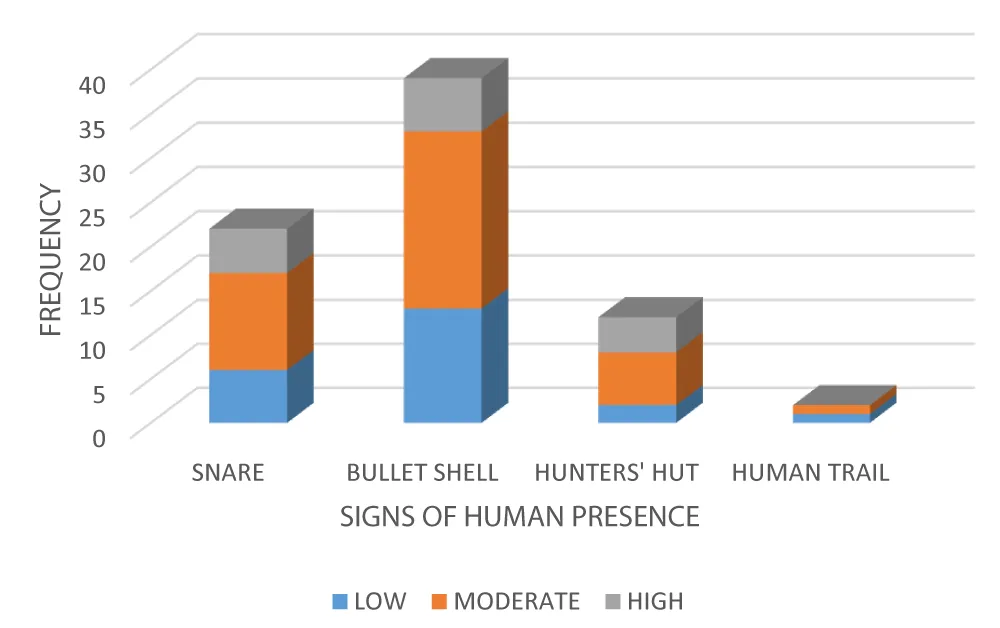

The presence of human activity in the pangolin ecosystem showed a significance on forest vegetation type X2 = 18.806 df = 9 p < 0.05 (Figure 2), forest vegetation canopy X2 = 10.528 df = 6 p < 0.05 (Figure 3), and forest undergrowth vegetation X2 = 6.877 df = 6 p < 0.05 (Figure 4), respectively. The influence of forest type and human presence in a pangolin environment can have significant implications for both the pangolins and their habitat. Considering the influence of forest type and human presence is essential for effective conservation and management of pangolins and their habitats. It requires a comprehensive approach that addresses the specific characteristics and challenges associated with different forest types, while also considering the socio-economic factors that drive human activities in these environments. Also, Human presence in a pangolin environment can lead to disturbances that affect the integrity and fragmentation of the forest vegetation canopy. Activities such as logging, agriculture, or infrastructure development can result in the removal or disruption of trees, causing gaps or openings in the canopy. This fragmentation can have negative consequences for pangolins, as it can reduce the availability of suitable habitat, alter microclimates, and disrupt the movement patterns of pangolins within their environment. Forest undergrowth vegetation can affect the preservation and visibility of human trails and footprints. In areas with thick undergrowth, human footprints may be quickly covered or obscured, making them less visible over time. On the other hand, in areas with sparse undergrowth or on well-established trails, human footprints may be more pronounced and easier to identify. The presence of dense undergrowth vegetation can impact human encounters with pangolins. Thick undergrowth can make it more challenging for humans to spot pangolins, potentially reducing the frequency of direct encounters. However, disturbances caused by humans moving through dense undergrowth can still disrupt pangolins' behavior and habitat use, even if they are not directly observed.

Different forest vegetation types provide varying levels of suitability for pangolins. Pangolins typically inhabit tropical and subtropical forests, including rainforests, deciduous forests, and mixed forests. The specific forest vegetation type influences factors such as food availability, shelter options, and microclimatic conditions. Human presence in different forest types impacts the availability and quality of habitat for pangolins, depending on the specific activities conducted and their effects on the forest ecosystem. The specific forest vegetation type can influence the types of human activities that occur in a pangolin environment. For example, certain forest vegetation types may be more attractive for poaching and agriculture due to the presence of a huge population of wildlife species or fertile soils. Conversely, protected areas or forests with conservation designations may have restrictions on human activities, limiting the intensity and extent of human presence. The compatibility between human activities and forest types determines the level of impact on pangolins and their habitat.

The forest vegetation canopy, which refers to the upper layer of tree branches and leaves that form a continuous cover, plays a crucial role in providing suitable habitat for pangolins. The canopy provides shade, protection, and resources such as food and shelter for pangolins. The presence of a dense and intact canopy is important for maintaining suitable conditions for pangolins to thrive. The relationship between the forest vegetation canopy and human presence is vital for effective conservation and management strategies in pangolin environments. Balancing human activities and the preservation of the canopy is crucial for maintaining the ecological integrity of the habitat and ensuring the long-term survival of pangolins.

Forest undergrowth refers to the vegetation and plant life that grows beneath the main canopy layer. The density and composition of the undergrowth can impact the visibility of human signs. Thick and dense undergrowth can obscure human trails, footprints, and other signs, making them less visible and harder to detect. Conversely, areas with sparse undergrowth can make human signs more apparent and easier to observe. However, the relationship between forest undergrowth vegetation and the presence of human activity provides insights into potential impacts on pangolins and their habitat. Balancing conservation efforts with sustainable land use practices is crucial to minimize negative impacts on pangolins while maintaining the integrity of the forest undergrowth and overall ecosystem.

Empty bullet shells 52% and snares 29% recorded the highest signs of human activity, while hunters’ hut 16% and hunting human trails 3% recorded the least (Figure 5), respectively. Pangolins are highly valued for their scales and meat in certain cultures, leading to illegal wildlife trade. The demand for pangolins and their derivatives drives poaching and trafficking, which poses a significant threat to pangolin populations. The presence of humans involved in illegal wildlife trade exacerbates the pressure on pangolins, contributing to population declines and pushing them closer to extinction. Efforts to combat illegal wildlife trade and raise awareness about the importance of pangolin conservation are crucial in mitigating this threat. In addition to the illegal wildlife trade, pangolins are also directly targeted by poachers and hunters for their meat or as a result of human-wildlife conflicts. Pangolins are often hunted for bushmeat consumption, traditional medicine, or as a source of income. The presence of humans engaged in poaching and hunting activities further endangers pangolin populations and disrupts their natural ecological balance.

Forest vegetation visibility recorded a significance on human signs, X2 = 3.162, df = 6, p < 0.05 (Figure 6).

Forest visibility refers to the extent to which the forest canopy and understory are clear and unobstructed. Forests with dense vegetation and a closed canopy have limited visibility, making it more challenging for humans to navigate through the forest and for human activities to be easily observed from outside. In contrast, forests with sparse vegetation or open canopies may have higher visibility, making human activities more visible to others. Forest visibility can influence human hunting and poaching activities in pangolin environments. Areas with low forest visibility may provide cover and concealment for illegal hunting and poaching, making it easier for individuals to engage in these activities undetected. Conversely, high forest visibility can act as a deterrent to illegal activities, as humans are more likely to be observed by others.

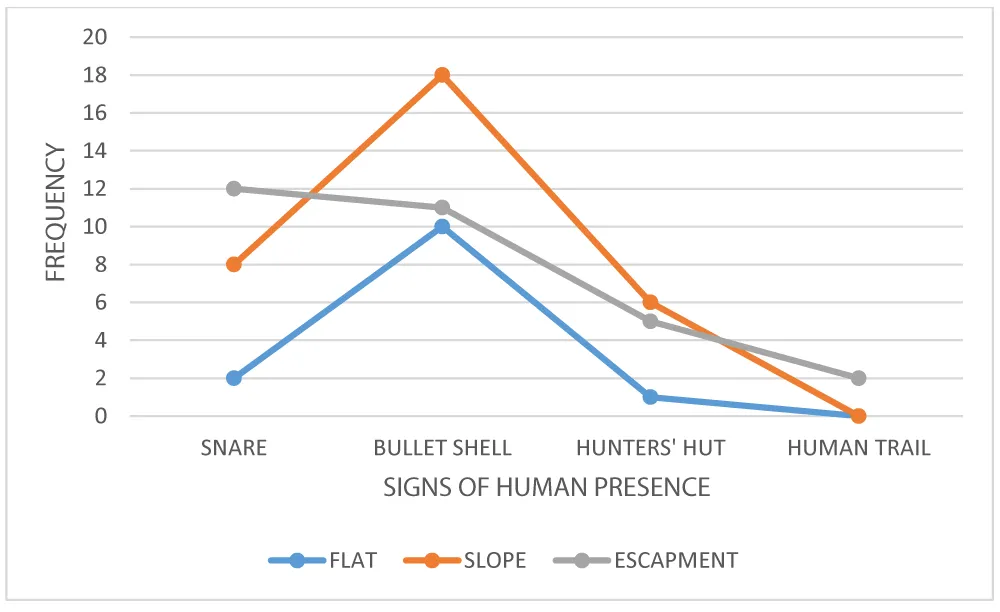

The forest vegetation landscape and human signs in pangolin environment showed a significant association, X2 = 8.972, df = 6, p < 0.05 (Figure 7). Human activity, like poaching, roads, and infrastructure development, in pangolin environments fragments forest landscapes and disrupts pangolin movement. These human signs create barriers that limit the connectivity between different forest patches, isolating pangolin populations and increasing the risk of genetic isolation and local extinction. Human settlements also lead to increased human-pangolin interactions, including hunting or capture for the illegal wildlife trade. Forest landscapes in pangolin environments can also be utilized for ecotourism initiatives, which can generate income for local communities and provide an incentive for the conservation of pangolins and their habitats. Responsible ecotourism practices raise awareness about the importance of pangolins and promote their conservation among visitors, contributing to the overall protection of forest landscapes.

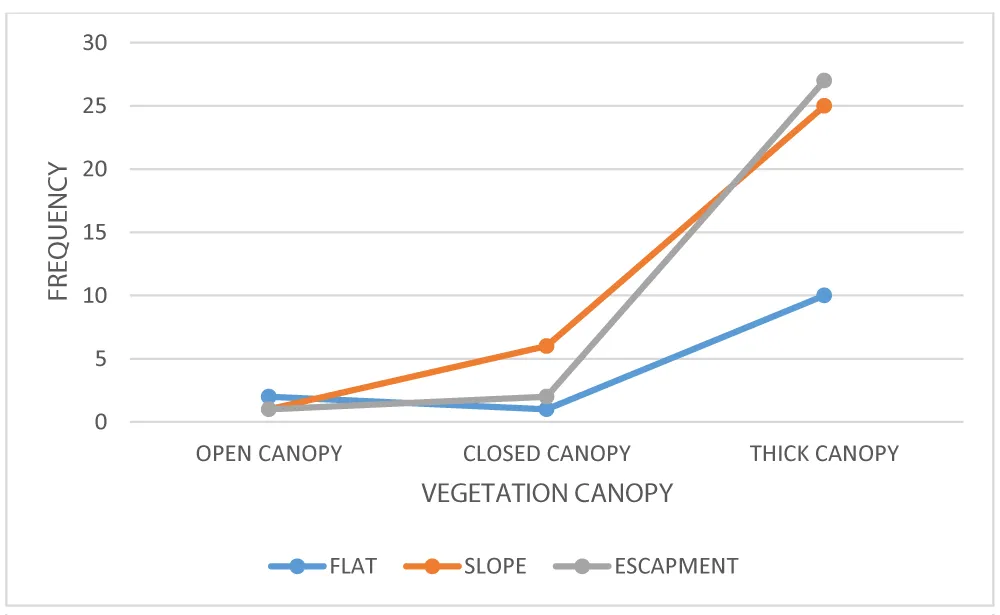

Forest canopy and landscape recorded a significant X2 = 5.434 df = 4 p < 0.05 (Figure 8). The heterogeneity of the forest landscape, which refers to the variety and spatial arrangement of different habitat types, can influence the diversity and structure of the forest vegetation canopy. Landscapes with a mix of different forest types, such as deciduous and coniferous forests, or a variety of tree species, can support a more diverse canopy structure and composition. Landscape heterogeneity provides a range of environmental conditions and resources, promoting species richness and enhancing the complexity of the forest vegetation canopy. The role of forest landscape on the forest vegetation canopy is crucial for effective forest management, conservation, and restoration efforts. By considering the landscape context, connectivity, and heterogeneity, it is possible to preserve and enhance the diversity, structure, and ecological functions of the forest vegetation canopy.

The atmospheric conditions revealed a positive association with human signs in the pangolin ecosystem, r = 0.108, p < 0.05 (Figure 9). The relationship between the atmosphere and human signs in a pangolin environment is more direct and significant compared to the relationship between the atmosphere and pangolin signs. Human signs, such as footprints, trails, settlements, and other forms of human activities, are influenced by atmospheric conditions in various ways. It's important to note that while atmospheric conditions influence human signs in a pangolin environment, the specific interactions between humans and pangolins are of greater significance for pangolin conservation. The presence of human signs in pangolin habitats often indicates human activities and potential threats to pangolins, such as habitat degradation, hunting, or illegal trade. Understanding and addressing these interactions is crucial for the conservation and protection of pangolins and their habitats.

Feeding 67%, earth-surface scratches 16%, and droppings 15% recorded the highest pangolin signs, while pangolin footprints 1% and trails 1% recorded the least (Figure 10) respectively. Significant presence of pangolin signs offers insights into the activity patterns of these elusive creatures. For example, tracks indicate the timing and frequency of their movements, whether they are nocturnal or diurnal, and the routes they take while foraging or traveling. By studying activity patterns through pangolin signs, researchers can better understand their behavior, resource utilization, and potential interactions with other species in the environment. Pangolin signs, particularly feeding signs, provide important information about their feeding ecology. Pangolins leave distinct signs when they feed on ant or termite nests, such as disturbed soil, broken ant or termite mounds, or characteristic feeding holes. By examining these signs, researchers gain insights into the types of prey species consumed, feeding techniques, and the ecological roles of pangolins in controlling ant and termite populations. Studying and interpreting pangolin signs is crucial for understanding the ecological role of pangolins, their interactions with the environment, and their conservation needs. It helps inform habitat management, protected area planning, and conservation efforts aimed at preserving pangolin populations and their habitats.

The pangolin sign age-rating recorded active sign 47%, recent sign 40%, and old sign 13% (Figure 11), respectively. The age of pangolin signs, such as tracks or burrows, provides valuable information about the presence and activity of pangolins in their environment. However, determining the precise age of a pangolin sign is challenging, and it often requires careful observation and interpretation of various factors. Observing signs associated with the pangolin sign provides additional information about its age. For instance, if there are signs of plant growth or regrowth around the burrow or tracks, it suggests that the sign has been present for a longer period. Similarly, if there are signs of animal scat or other indications of recent feeding activity nearby, it may suggest a more recent occurrence. The freshness of the pangolin sign gives a rough estimate of its age. Fresh tracks or burrows that show no signs of weathering or disturbance are likely to be more recent. On the other hand, if the sign appears weathered, covered in debris, or shows signs of erosion, it suggests that it has been present for a longer period.

Discussion

Anthropogenic interference, such as poaching, deforestation, agricultural expansion, and logging, has led to significant habitat degradation and fragmentation within the rainforest of Cameroon. The loss of forest cover and alteration of vegetation composition have directly impacted the availability of suitable habitats for pangolins. Pangolins are mammals that have been facing high extinction risk due to increasing levels of poaching of different species to feed local/regional wildlife markets, fueled by the exponential international demand for African species in particular [9,15]. The trade, mainly focused on Asian species in the late 20th century, has shifted to African pangolins in the 21st century since Asian pangolins severely declined during thethe pre-2000 period [9]. During the last decade (2010 – 2019), more than 400,000 individuals of African pangolins were involved in the illegal international trade [9]. The white-bellied (Phataginus tricuspis) and giant (Smutsia gigantea) pangolins were the most targeted species [9,11-13,17]. Beside the illegal international trade [9,12,17,21], African pangolins underwent an unprecedented degradation of their habitats, especially in Western Africa where > 80 % of forest cover vanished over the last century [30].

In Africa, wild meat (non-domesticated animals) is an important source of animal protein and income for local people [31-34]. Wild animals are openly sold in the bushmeat and traditional medicine markets [35,36] that represent a great threat to African’s wildlife [34,36] but also to human health [37]. Among specimens sold in these markets occur pangolin species and many other threatened species present on the IUCN Red List [35]. National and international trade can drive a species to extinction [7]. Local use in pangolins for consumption and traditional medicine, combined with inter-regional and international trade in an unregulated context, certainly emphasizes the depletion of African pangolins. The latter may also suffer from fragmented and isolated populations by infrastructure development and agriculture that could rapidly lead to irreversible local extinctions [38,39]. Although the illegal pangolin trade is widely acknowledged to be the major threat to the conservation of pangolins globally and African pangolins in particular [9,10], these data are not sufficient to mitigate the ongoing decline of all eight species. They are still ecologically and genetically data-poor species with a great gap of knowledge [12,40] that hampers effective conservation actions. The research findings highlight the devastating impacts of illegal hunting caused by the wildlife trade on pangolins in the park. The demand for pangolin scales and meat in traditional medicine practices and culinary preferences has driven the unsustainable harvest of these animals.

The lack of ecological knowledge is certainly related to the cryptic and elusive behaviour of pangolins [41,42], making it challenging the bio monitor the species [43-45]. The phylogeny and population genetics of African pangolins have been previously addressed [46,47], but these studies were based on limited data globally without precision of sampled forest habitats. Nevertheless, the study has important implications for the development of conservation strategies and management plans within Deng Deng National Park. The discussion highlights the need for integrated approaches that address both the direct threats to pangolins, such as hunting and trade, and the underlying drivers, including poverty, lack of awareness, and weak law enforcement. It emphasizes the importance of community engagement, sustainable livelihood initiatives, and education programs to foster local support for pangolin conservation. Additionally, the discussion explores the potential for protected area design, habitat restoration, and the implementation of stricter regulations to mitigate the interference of human activity.

Conclusion

Anthropogenic interference in the pangolin environment within Deng Deng National Park poses significant threats to the survival of these unique and endangered creatures. The study emphasized the need for immediate action to protect pangolins and their habitats by implementing conservation strategies, strengthening law enforcement, and engaging local communities. By addressing the underlying drivers and mitigating the threats of habitat degradation, illegal hunting, and trade, it is possible to ensure the long-term viability of pangolin populations and preserve the ecological integrity of Deng Deng National Park. By mitigating the threats posed by habitat degradation, illegal hunting, and trade, it is possible to protect these unique and endangered creatures and preserve the ecological integrity of the park. Continued research and collaborative efforts are crucial to further our understanding of the complex interactions between human activities, pangolins, and their habitats, guiding conservation actions and promoting sustainable coexistence. Continued research, monitoring, and collaboration among stakeholders are vital for achieving these conservation goals and promoting sustainable coexistence between humans and pangolins. Pangolins play a crucial role as insectivores, contributing to the ecological balance by controlling insect populations. The decline in pangolin populations disrupts this balance, leading to potential ecological cascades. Understanding and mitigating these ecological implications are essential for preserving the overall biodiversity and functioning of the forest ecosystem within the national park.References

- Gaubert P, Wible JR, Heighton SP, Gaudin TJ. Chapter 2 - Phylogeny and systematics. In: Challender DWS, Nash HC, Waterman C, editors. Pangolins. Academic Press; 2020;25–39. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128155073000022 (accessed December 13, 2021).

- Pages E. The scent glands of arboreal pangolins (M. tricuspis and M. longicaudata): morphology, development and roles. Biologia Gabonica. 1968;4:353–400.

- Pietersen D, Jansen R, Swart J, Kotze A. A conservation assessment of Smutsia temminckii. In: The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust; 2016;1–11. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311675419_A_conservation_assessment_of_Smutsia_temminckii

- Cabana F, Plowman A, Van Nguyen T, Chin S-C, Wu S-L, Lo H-Y, et al. Feeding Asian pangolins: An assessment of current diets fed in institutions worldwide. Zoo Biology. 2017;36:298–305.

- Hoffmann M, Nixon S, Alempijevic D, Ayebare S, Bruce T, Davenport TRB, et al. Chapter 10 - Giant pangolin Smutsia gigantea (Illiger, 1815). In: Challender DWS, Nash HC, Waterman C, editors. Pangolins. Academic Press; 2020a;157–173. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128155073000101 (accessed November 11, 2021).

- Jansen R, Sodeinde O, Soewu D, Pietersen DW, Alempijevic D, Ingram DJ. Chapter 9 - White-bellied pangolin Phataginus tricuspis (Rafinesque, 1820). In: Challender DWS, Nash HC, Waterman C, editors. Pangolins. Academic Press; 2020;139–156. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128155073000095 (accessed November 11, 2021).

- Morton O, Scheffers BR, Haugaasen T, Edwards DP. Impacts of wildlife trade on terrestrial biodiversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2021;5:540–548.

- Aditya V, Goswami R, Mendis A, Roopa R. Scale of the issue: Mapping the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on pangolin trade across India. Biological Conservation. 2021;257:109136.

- Challender DWS, Heinrich S, Shepherd CR, Katsis LKD. Chapter 16 - International trade and trafficking in pangolins, 1900–2019. In: Challender DWS, Nash HC, Waterman C, editors. Pangolins. Academic Press; 2020;259–276. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128155073000162 (accessed August 8, 2021).

- Challender DWS, Harrop SR, MacMillan DC. Understanding markets to conserve trade-threatened species in CITES. Biological Conservation. 2015;187:249–259. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.04.015

- Mwale M, Dalton DL, Jansen R, De Bruyn M, Pietersen D, Mokgokong PS, Kotzé A. Forensic application of DNA barcoding for identification of illegally traded African pangolin scales. Genome. 2017;60:272–284. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1139/gen-2016-0144

- Ingram DJ, Cronin DT, Challender DWS, Venditti DM, Gonder MK. Characterising trafficking and trade of pangolins in the Gulf of Guinea. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2019;17:e00576. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00576

- Zhang H, Ades G, Miller MP, Yang F, Lai K, Fischer GA. Genetic identification of African pangolins and their origin in illegal trade. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2020;23:e01119. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01119

- Ingram DJ, Coad L, Abernethy KA, Maisels F, Stokes EJ, Bobo KS, Breuer T, Gandiwa E, et al. Assessing Africa-wide pangolin exploitation by scaling local data. Conservation Letters. 2018;11:e12389. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12389

- Heinrich S, Wittmann TA, Prowse TAA, Ross JV, Delean S, Shepherd CR, Cassey P. Where did all the pangolins go? International CITES trade in pangolin species. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2016;8:241–253. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.09.007

- Boakye MK, Kotze A, Dalton D, Jansen R. Unravelling the pangolin bushmeat commodity chain and the extent of trade in Ghana. Human Ecology. 2016;44:257–264. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9813-1

- Mambeya MM, Baker F, Momboua BR, Koumba Pambo AF, et al. The emergence of a commercial trade in pangolins from Gabon. African Journal of Ecology. 2018;56:601–609. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12507?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Nixon S, Pietersen D, Challender D, Hoffmann M, Godwill I, Bruce T, Ingram DJ, Shirley MH. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Smutsia gigantea. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; 2019. Available from: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en (accessed November 1, 2021).

- Pietersen D, Moumbolou C, Ingram DJ, Soewu D, Jansen R, Sodeinde D, Iflankoy KLM, Challender D, Shirley MH. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Phataginus tricuspis. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; 2019. Available from: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en (accessed August 8, 2021).

- Akpona HA, Djagoun CAMS, Sinsin B. Ecology and ethnozoology of the three-cusped pangolin Manis tricuspis (Mammalia, Pholidota) in the Lama forest reserve, Benin. Mammalia. 2008;72:198–202. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1515/MAMM.2008.046?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Zanvo S, Djagoun SCAM, Azihou FA, Djossa B, Sinsin B, Gaubert P. Ethnozoological and commercial drivers of the pangolin trade in Benin. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2021;17:18. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13002-021-00446-z

- Zanvo S, Gaubert P, Djagoun CAMS, Azihou AF, Djossa B, Sinsin B. Assessing the spatiotemporal dynamics of endangered mammals through local ecological knowledge combined with direct evidence: the case of pangolins in Benin (West Africa). Global Ecology and Conservation. 2020;23:e01085. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01085

- Schneider M. Habitat loss, fragmentation and predator impact: spatial implications for prey conservation. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2001;38:720–735. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00642.x?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Fischer J, Lindenmayer DB. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: a synthesis. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2007;16:265–280. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00287.x

- Collinge S. Spatial ecology and conservation. Nature. 2010;3:69. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284377162_Spatial_Ecology_and_Conservation

- Horváth Z, Ptacnik R, Vad CF, Chase JM. Habitat loss over six decades accelerates regional and local biodiversity loss via changing landscape connectance. Ecology Letters. 2019;22:1019–1027. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13260

- Mercy ND. The effects of habitat heterogeneity and human influences on the diversity, abundance, and distribution of large mammals: the case of Deng Deng National Park, Cameroon. PhD thesis. Brandenburg University of Technology, Cottbus-Senftenberg, Germany; 2015;2–24. Available from: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-btu/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/3571/file/Diangha+Mercy.pdf

- Fotso R, Eno N, Groves J. Distribution and conservation status of the gorilla population in the forests around Belabo, Eastern Province, Cameroon. Cameroon Oil Transportation Company (COTCO) and Wildlife Conservation Society; 2002;58. Available from: https://africanelephantdatabase.org/system/population_submission_attachments/files/000/001/244/original/Fotso_et_al_2002_Forests_around_Belabo_COTCO_small.pdf

- COTCO. Specific Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA) for the interaction between The Chad-Cameroon Pipeline Project and the Lom Pangar Dam Project: SEIA Lom Pangar pipeline. 2011;232. Available from: https://energypedia.info/images/c/c5/Cameroon_Lom_Pangar_Hydropower_Project_E%26FA.pdf

- Aleman JC, Jarzyna MA, Staver AC. Forest extent and deforestation in tropical Africa since 1900. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2018;2:26–33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0406-1

- Fa JE, Peres CA, Meeuwig J. Bushmeat exploitation in tropical forests: an intercontinental comparison. Conservation Biology. 2002;16:232–237. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00275.x

- Codjia JTC, Assogbadjo AE. Mammalian wildlife and diet of the Holli and Fon populations of the Lama classified forest (Southern Benin). Cahiers Agricultures. 2004;13:341–347. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233859261_Faune_sauvage_mammalienne_et_alimentation_des_populations_holli_et_fon_de_la_foret_classee_de_la_Lama_au_Sud-Benin

- McNamara J, Kusimi JM, Rowcliffe JM, Cowlishaw G, Brenyah A, Milner-Gulland EJ. Long-term spatio-temporal changes in a West African bushmeat trade system. Conservation Biology. 2015;29:1446–1457. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12545

- Ingram DJ, Coad L, Milner-Gulland EJ, Parry L, Wilkie D, Bakarr MI, et al. Wild meat is still on the menu: progress in wild meat research, policy, and practice from 2002 to 2020. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2021;46:221–254. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-041020-063132

- Djagoun CAMS, Akpona H, Mensah G, Sinsin B, Nuttman C. Wild mammals traded for zootherapeutic and mythic purposes in Benin (West Africa): capitalizing species involved, provision sources, and implications for conservation. In: Alves RRN, Rosa IL, editors. Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine. Springer-Verlag; 2013;267–381. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29026-8_17

- D’Cruze N, Assou D, Coulthard E, Norrey J, Megson D, Macdonald DW, Harrington LA, Ronfot D, Segniagbeto GH, Auliya M. Snake oil and pangolin scales: insights into wild animal use at “Marché des Fétiches” traditional medicine market, Togo. Nature Conservation. 2020;39:45–71. Available from: https://natureconservation.pensoft.net/article/47879/

- Zanvo S, Djagoun CAMS, Azihou AF, Sinsin B, Gaubert P. Preservative chemicals as a new health risk related to traditional medicine markets in western Africa. One Health. 2021;13:100268. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100268

- Reed DH, O’Grady JJ, Brook BW, Ballou JD, Frankham R. Estimates of minimum viable population sizes for vertebrates and factors influencing those estimates. Biological Conservation. 2003;113:23–34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00346-4

- Clabby C. A magic number? American Scientist. 2010;98:24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1511/2010.82.24

- Heighton SP, Gaubert P. A timely systematic review on pangolin research, commercialization, and popularization to identify knowledge gaps and produce conservation guidelines. Biological Conservation. 2021;256:109042. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109042

- Heath ME, Coulson IM. Preliminary studies on relocation of Cape pangolins Manis temminckii. South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 1997;27:51–56. Available from: https://www.conservationevidence.com/individual-study/7605

- Willcox D, Nash HC, Trageser S, Kim HJ, Hywood L, Connelly E, et al. Evaluating methods for detecting and monitoring pangolin (Pholidota: Manidae) populations. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2019;17:e00539. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00539

- Cunningham RB, Lindenmayer DB. Modeling count data of rare species: some statistical issues. Ecology. 2005;86:1135–1142. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1890/04-0589

- Lomba Â, Pellissier L, Randin C, Vicente J, Moreira F, Honrado J, et al. Overcoming the rare species modelling paradox: a novel hierarchical framework applied to an Iberian endemic plant. Biological Conservation. 2010;143. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320710003137

- Singhal S, Hoskin CJ, Couper P, Potter S, Moritz C. A framework for resolving cryptic species: a case study from the lizards of the Australian Wet Tropics. Systematic Biology. 2018;67:1061–1075. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syy026

- Gaubert P, Antunes A, Meng H, Miao L, Peigné S, Justy F, et al. The complete phylogeny of pangolins: scaling up resources for the molecular tracing of the most trafficked mammals on Earth. Journal of Heredity. 2018;109:347–359. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esx097

- Du Toit Z, Dalton DL, Du Plessis M, Jansen R, Grobler JP. Isolation and characterization of 30 STRs in Temminck’s ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii) and potential for cross amplification in other African species. Journal of Genetics. 2020;99:20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32366731/

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley