Annals of Limnology and Oceanography

Amur Estuary in the Mirror of Secular Variability (1896-2021)

1V.I. Il’ichev Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far East Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia

Author and article information

Cite this as

Vlasova GA, et al. Amur Estuary in the Mirror of Secular Variability (1896-2021). Ann Limnol Oceanogr. 2026; 11(1): 001-004. Available from: 10.17352/alo.000021

Copyright License

© 2026 Vlasova GA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.The Amur Liman is a unique bipolar estuarine system that functions as a hydraulic link between the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan. Using a synthesis of long-term hydrological observations (1896–2021) and satellite remote sensing (MODIS/Terra and Aqua), this study examines the secular variability of discharge, circulation patterns, and climate-driven hydrodynamic restructuring in the Amur estuary. The analysis demonstrates that Liman dynamics are governed by the interaction between the Siberian High and the Far Eastern monsoon system, which together regulate ice regimes, seasonal runoff, and extreme flood events. Particular attention is given to tidal interference, flow bifurcation at Cape Pronge, and the formation of the so-called “Amur Loop,” highlighting the role of baroclinic effects and basin morphology in shaping circulation. Long-term discharge phase analysis reveals that extreme floods are synchronized with secular climatic signals rather than representing stochastic anomalies. These results frame the Amur Liman as a sensitive climate indicator system, with important implications for future coastal management, flood risk assessment, and regional environmental monitoring under conditions of accelerating climatic variability.

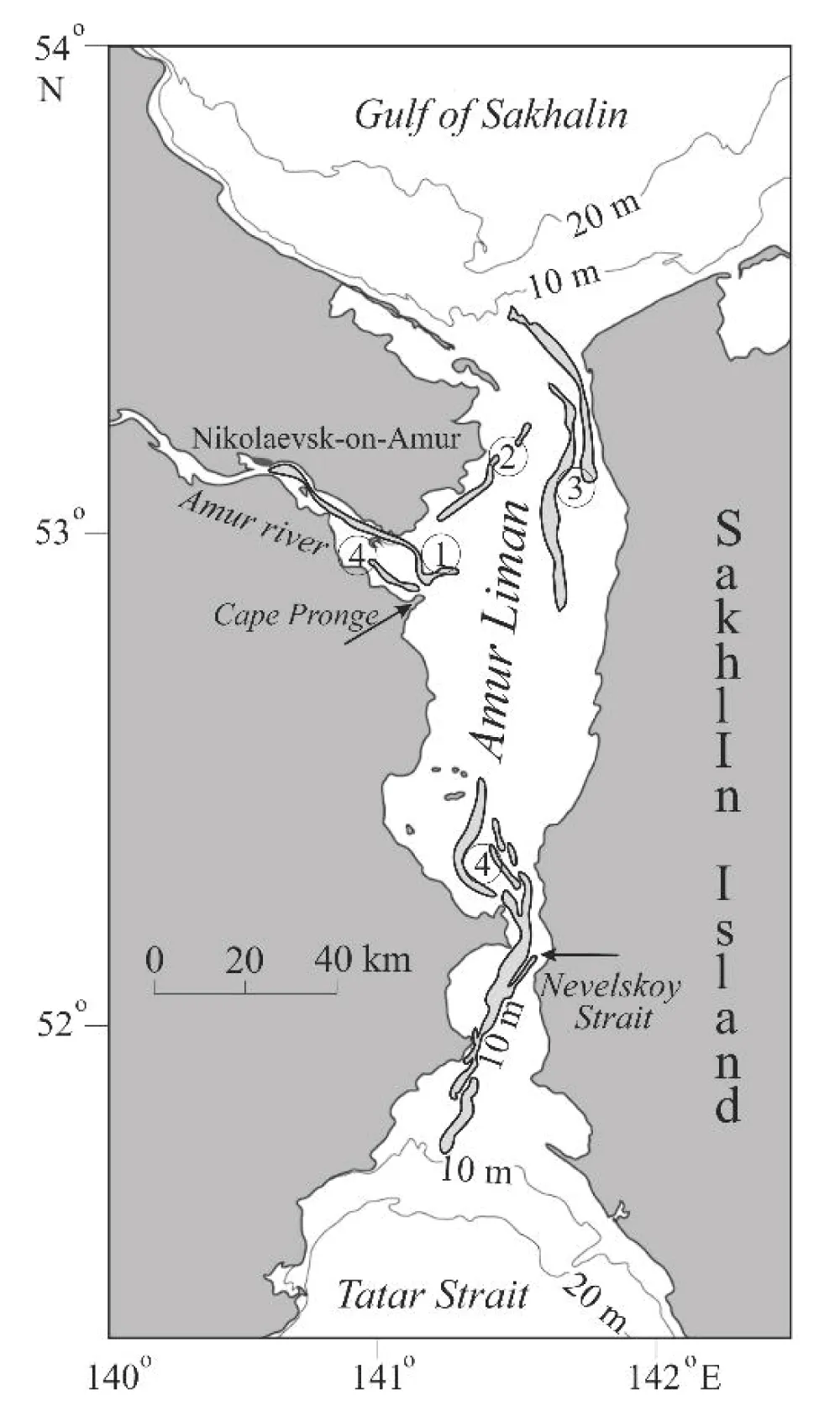

The Amur Liman is a unique bipolar estuarine ecosystem that functions as a hydraulic lock connecting the waters of the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan (Figure 1). This shallow-water basin is coupled with the mouth area of the Amur River, one of the largest rivers in East Asia. The Liman extends meridionally for ~185 km with a width of 40 km and an average depth of only 4–6.5 m, which sharply contrasts with the depths at its boundaries: up to 15 m in the north (the Sea of Okhotsk) and up to 10 m in the south (the Nevelskoy Strait). This morphological uniqueness, combined with the complex seafloor topography, determines its specific hydrological regime. Within this framework, the Amur Liman functions as a large-scale estuarine converter, transforming and mixing the opposing flows of riverine and marine waters [1,2].

The underwater delta of the Amur is dissected by a system of banks and shoals into distinct fairways that dictate the regional hydrodynamics, which, given the extreme inaccessibility of the coastline, characterized by vast tidal flats and a lack of transport infrastructure, significantly limits the scope of continuous on-site (in situ) observations. In this connection, an empirical basis of research was created, which integrates long-term hydrological records and high-resolution remote sensing data. River discharge series (1896–2021) were obtained from the Roshydromet gauging stations (Khabarovsk and Bogorodskoye), providing a robust historical baseline. These were synthesized with satellite monitoring archives (MODIS/Terra and Aqua, 2004–2011) to analyze the spatial evolution of the Amur plume. Consequently, the integration of century-scale gauge data with satellite imagery serves as the most reliable methodology for ensuring spatial and temporal reproducibility in this geographically challenging region.

A primary indicator of riverine influence, alongside density gradients, is the thermal structure of the surface waters. During periods of low dynamic intensity, a river plume (with a thickness of 5–10 m) forms within the Liman and the Sakhalin Gulf, buoyantly spreading atop the denser marine water masses. The resulting pronounced vertical density and temperature gradients (the pycnocline and thermocline) effectively block vertical exchange, thereby governing the hydrochemical and biological status of the coastal waters [3-5].

The regional hydrophysical regime is governed by a direct coupling between the Far Eastern monsoon system and estuarine dynamics. Meridional atmospheric circulation and abrupt shifts in pressure fields act as the primary drivers of the Liman’s seasonal variability [6,7]. During winter, the intensified Siberian High creates a stable ‘ice corridor,’ where northwesterly flows transport Arctic air masses, triggering early-onset ice formation and transforming the Liman into a monolithic platform that suppresses wind-driven mixing [8]. Conversely, the summer-autumn runoff intensity is strictly dictated by the development of the Far Eastern Low [9,10]. This pressure configuration directs the summer monsoon to shape the Amur’s specific hydrograph, where up to 90% of the annual discharge is concentrated. Thus, the Siberian High and the Far Eastern monsoon system function as a unified climatic regulator, simultaneously dictating the ice regime’s stability and the catastrophic nature of monsoon-driven floods.

Transition phases of circulation (May and October) are localized within narrow time intervals, marking a radical restructuring of the regional hydrodynamics.

Annually, the Amur River delivers a substantial volume of resources to the Liman system: over 350–380 km³ of freshwater and approximately 52 million tons of suspended sediment. The intra-annual dynamics of this discharge are extremely asymmetrical, with up max of the runoff concentrated within the narrow window of the summer monsoons from May to October [7,11]. The hydrological regime is controlled by a superposition of a weak spring snowmelt and prevailing summer-autumn rain floods. The primary runoff pulse occurs between July and September; its amplitude is directly dictated by the intensity of monsoon circulation and moisture transport from deep cyclones and tropical typhoons [12-14].

Water circulation in the Amur Liman is driven by a triad of factors: river discharge, tidal energy, and wind forcing. During the ice-free period, the wind acts as a dynamic redistributor of water masses. The hydrodynamic regime of the area is quasi-permanent: multidirectional flows are recorded along the coasts, generated by both the Amur discharge and the inter-basin sea-level gradient between the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan [15].

Historically, the first fundamental circulation scheme, reconstructed from the Far Eastern Regional Hydrometeorological Research Institute (DVNIGMI) data for 1933–1940, remains the baseline for discussion [16]. According to this classical model, cold waters from the Sea of Japan advance along the eastern coast, while the Okhotsk masses shift southward along the western shore. However, this scheme describes only the background circulation, neglecting the powerful impulse of the Amur discharge. The specific hydrodynamics of the Liman are determined by the interference of the Okhotsk and Japan Sea tidal waves. In conditions of extreme shallowness and a labyrinth of fairways, this leads to an anomalous increase in current velocities within bottlenecks. It is the tides that act as the primary regulator here, ensuring forced water exchange through the Nevelskoy Strait [17,18].

An alternative circulation model, presented in the Lotsiya Tatarskogo proliva... [1], confirms the meridional orientation of the main discharge toward the Sakhalin Gulf but identifies a crucial bifurcation zone at Cape Pronge. Here, the hydrodynamic structure is governed by the interference of tidal waves and baroclinic effects, leading to a complex restructuring of the flow. While part of the Amur water transits into the Sea of Japan through the Nevelskoy Strait, another significant portion forms a local cycle within the Liman, forcibly returning to the northern circulation due to the Eastern fairway’s configuration. This mechanism, effectively closing the “Amur Loop,” indicates that the regional dynamics are dictated by density-driven gradients and the Coriolis force rather than oversimplified wind-drift models.

Fundamental studies of the Amur estuary [Gidrologiya ust’evoy oblasti r. Amur [19] confirms that the general water transport is determined by the configuration of the fairways. The distribution of discharge among the primary arteries (the Northern, Eastern, and Southern fairways), according to calculations by Yakunin [20] and Ponomareva [21], is nearly proportional (averaging 30% - 40% per channel), proving the decisive role of seafloor morphology. However, this system is not static: it represents a pulsating mechanism where proportions vary depending on river volume and wind regime. Northerly winds during transition periods increase the fraction of discharge moving south (the surge effect), whereas the summer southerly monsoon traps fresh water masses in the northern Liman, promoting their discharge into the Sakhalin Gulf [14,22].

The consensus of modern researchers [2,23,24] confirms the dominance of the northward transport vector. This priority is dictated by the basin’s geometry: the Amur mouth is shifted toward the Sakhalin Gulf, and the width of the northern opening (24 km) is three times that of the Nevelskoy Strait’s bottleneck (7 km). Consequently, the bulk of the discharge is carried into the Sakhalin Gulf, forming a large-scale East Sakhalin freshwater plume that pulsates in sync with the river’s volume. An additional driver for this meridional drift is the inter-basin sea-level difference: the summer monsoon creates a northward slope, intensifying the water discharge into the Sea of Okhotsk. However, in a shallow bipolar estuary, baroclinic effects and the Coriolis force play a key role. The interaction of diverse water masses generates a complex vortex structure that determines the Liman’s hydrodynamics more accurately than standard drift models [25,26].

A synthesis of nearly a century of data has allowed us to construct a comprehensive circulation scheme. According to this model, the primary freshening arteries are channeled through the Northern and Sakhalin fairways. The southern vector retains its significance, but its structure is more complex: a critical flow reversal occurs near Cape Pronge, where the configuration of the Eastern fairway forcibly returns part of the discharge to the northern circulation, thus closing the “Amur Loop.”

Despite the existence of general schemes, circulation in the Liman remains a subject of intense debate. Research records not a static flow but high-frequency oscillations: the Amur discharge pulsates, reorienting between the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan in response to short-term impulses [15]. Satellite monitoring (2004–2011) confirms the stochastic nature of the process [2]: out of 40 analyzed cases, a northward vector was recorded in only 17, a southward vector in 6, and in 14 cases, no significant discharge was observed, indicating periods of stagnation or intensive internal mixing. The Liman’s dynamics remain strictly dictated by the monsoon calendar.

A detailed segmentation of the open-water season [27] demonstrates that while northward meridional transport dominates during the peak summer monsoon (June–August), the autumn restructuring of atmospheric circulation (September–October) acts as a ‘reversal trigger’, forcibly redistributing Amur waters. The differentiation between the ‘cold’ (May–July) and ‘warm’ (July–September) monsoon phases confirms that regional hydrodynamics are a function of the atmosphere’s thermal state [28]. Historical data (1980–1988) record an alternative pattern: the warmed waters of the Liman shifted primarily along the western coast of Sakhalin Island, while the mainland shore was occupied by cold Okhotsk masses [3]. This provides direct evidence that the system is capable of switching between stable circulation regimes, forming long-lived hydrophysical anomalies.

Under standard conditions, the hydrodynamic background of the Amur Liman is characterized by moderate dynamics, with current velocities ranging from 0.35 to 0.9 m/s [19] and low-amplitude oscillations [15]. This picture serves merely as a ‘baseline background’, which undergoes radical deformation during periods of floods and typhoons [29]. The regional dynamics are not autonomous; they are governed by a cascade of external drivers: from surge-driven fluctuations [30,31] and tidal cycles [1,27] to the inter-basin sea-level gradient [3,32,33]. In this system, the Liman acts as a membrane, reacting to the overall scale of water exchange between the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk [5,34].

The discharge regime of the Amur River serves as an indicator of regional climatic shifts. The assessment of extreme flood frequency remains a subject of debate: the interval between catastrophic events varies from 7–8 years for the Middle Amur to 15 years for the Lower Amur [7,35]. To resolve these contradictions, this study relies on a comprehensive 126-year observation series (1896–2021). The analysis of this dataset [36] has enabled the identification of long-term discharge phases. To clearly distinguish between baseline hydrodynamics and extreme events, we analyzed these long-term phases to show that extreme floods are not stochastic anomalies but are synchronized with secular climatic signals, while the baseline background is characterized by moderate seasonal pulses. This 126-year retrospective demonstrates that the modern period of intensification in hydrological anomalies is part of a broader transition between stable discharge phases, reflecting a fundamental shift in the Far Eastern moisture transport system.

Thus, a retrospective of observations spanning more than a century allows us to interpret the Amur Liman not merely as a transit zone but as a robust dynamic mirror of the Far Eastern ecosystem—a pulsating heart of the region, whose rhythms reflect the secular variability of the climate.

Conclusion

The synthesis of century-scale hydrological records and modern satellite data reveals that the Amur Liman functions not merely as a transit estuary but as a critical climate indicator system for the Far Eastern region. Our findings confirm that Liman’s hydrodynamics are strictly governed by a unified climatic regulator: the interaction between the Siberian High and the Far Eastern monsoon. The identification of the “Amur Loop” and the pulsatory discharge regimes across primary fairways demonstrates that the system is highly sensitive to secular climatic shifts.

The 126-year retrospective (1896–2021) indicates that extreme hydrological events are synchronized with long-term atmospheric signals, making the Liman a robust dynamic mirror of regional moisture transport. For future coastal management and regional research, this implies a necessity to shift from static circulation models to dynamic, event-based monitoring. Given the coastal inaccessibility, further integration of remote sensing with high-frequency gauge data is vital for predicting catastrophic floods and managing the fragile bipolar ecosystem of the Amur estuary in an era of accelerating climatic variability.**

- Sailing directions for the Tatar Strait, the Amur Liman, and the La Perouse Strait. St. Petersburg: GUNiO MO; 2003;436.

- Osadchiev AA. Spreading of the Amur River plume in the Amur Liman, the Sakhalin Gulf, and the Tatar Strait. Oceanology. 2017;57(3):392–401. doi:10.1134/S000143701703014X.

- Rostov ID, Zhabin IA. Hydrological features of the Amur River mouth area. Meteorol Hydrol. 1991;(7):74–78.

- Zhabin IA, Abrosimova AA, Dubina VA, Nekrasov DA. The influence of the Amur River runoff on the hydrological conditions of the Amur Liman and the Sea of Okhotsk. Meteorol Hydrol. 2010;(4):93–100. doi:10.3103/S106837391004008X.

- Andreev AG. Distribution of desalinated waters of the Amur Liman in the Sea of Okhotsk according to satellite observations. Izv Atmos Ocean Phys. 2019;55(9):1160–1165. doi:10.1134/S000143381909003X.

- Il’inskiy OK, Egorova MV. Cyclonic activity over the Sea of Okhotsk during the cold half-year. Trudy DVNIGMI. 1962;(14):34–38.

- Metal’nikov AA. The regime of the lower Amur bars under the conditions of the extreme flood of 2013. Gidrotekhnicheskoe stroitel'stvo. 2017;(10):12–19.

- Yakunin LP. Variability of ice cover in the Far Eastern seas of Russia. Izvestiya TINRO. 2012;171:222–231.

- Novorotskiy PV. Monsoon distribution over the southern part of the Russian Far East. Russ Meteorol Hydrol. 1999;(11):31–36.

- Vasilevskaya LN, Shtatskaya LE, Shapovalov SM. Features of atmospheric circulation during the formation of extreme floods in the south of the Far East. Trudy DVNIGMI. 2011;(111):3–14.

- Reprintseva YuS. Features of natural conditions of the Amur River mouth area. Issues of Geography of the Upper Amur Region. 2020;(7):233–236.

- Kalugin AS. Model of the Amur River runoff formation and its application for assessing possible changes in the water regime [doctoral dissertation]. Moscow: Institute of Water Problems, Russian Academy of Sciences; 2016;185.

- Makhinov AN. Modern channel formation in the lower reaches of the Amur. Vladivostok: Dalnauka; 2013;163.

- Dubinina VG, Makhinov AN, Konovalova NV. Features of the formation of water and sediment runoff in the Amur River basin. Water Resour. 2020;47(6):647–658. doi:10.1134/S009780782006004X.

- Ivanova EV, Ivanov VV. Formation of the Amur runoff in the Amur Liman. Russ Meteorol Hydrol. 2012;37(9):606–614. doi:10.3103/S106837391209004X.

- Danchenkov MA, Volkov RN, Oleynikov SA. Oceanography of the Tatar Strait. Vladivostok: Dalnauka; 2005;250.

- Shevchenko GV. Features of tidal sea level fluctuations in the Amur Liman. Russ Meteorol Hydrol. 2004;(6):56–63.

- Medvedev IP, Rabinovich AB, Kulikov EA. Tides in the Sea of Okhotsk: Results of numerical modeling. Oceanology. 2018;58(2):173–185. doi:10.1134/S000143701802009X.

- Hydrology of the Amur River mouth area. Amur. Trudy DVNIGMI. Vladivostok; 1977. (29):560.

- Yakunin LP. Distribution of water runoff along the fairways of the Amur mouth. Trudy DVNIGMI. 1978;(71):162–166.

- Ponomareva TG. Distribution of water and sediment runoff along the fairways of the Amur Liman. Trudy DVNIGMI. 1982;(96):102–110.

- Rostov ID, Rudykh NI, Rostov VI. Information system on oceanography of the Far Eastern region. Russ Meteorol Hydrol. 2001;(12):65–73.

- Kolpakov NV. Current state of the Amur River estuary ecosystem under conditions of runoff and climate change. Readings in Memory of Vladimir Yakovlevich Levanidov. 2022;(9):115–124.

- Chernyavskiy IV. Hydrological regime of coastal waters of the Sea of Okhotsk in the Amur Liman area. Oceanology. 2022;62(4):455–467. doi:10.1134/S0001437022040050.

- Osadchiev AA. Dynamics and variability of river plumes in the Arctic and Far Eastern seas of Russia [doctoral dissertation abstract]. Moscow: Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences; 2018;46.

- Nazirov MG, Kulikov EA. Modeling of baroclinic circulation in the mouth areas of large rivers of the Far East. Izv Atmos Ocean Phys. 2023;59(1):93–105. doi:10.1134/S0001433823010077.

- Strobykina AA, Zhabin IA, Kim VI, Shul’kin VM, Dudarev OV. Features of hydrological processes in the Amur Liman. Water Resour. 2016;43(4):481–491. doi:10.1134/S0097807816040103.

- Vasilevskaya LN, Shkaberda OA, Lamash BE, Platonova VA, Kukarenko EA. Features of long-period variability of temperature, precipitation and the timing of the second stage of the summer monsoon in Peter the Great Bay. Vestnik DVO RAN. 2013;(6):71–82.

- Shalygin AL, Dugina IO. The catastrophic flood of 2013 in the Amur basin: Causes, features, consequences. In: Georgievskiy VYu, editor. Extreme floods in the Amur basin: Hydrological aspects. St. Petersburg: EsPeKha; 2015;22–35.

- Savel’ev AV. Surge fluctuations of the sea level in the Sakhalin Gulf. In: Hydrometeorological and ecological conditions of the Far Eastern seas: Environmental impact assessment. Thematic issue No. 3. Vladivostok: Dalnauka; 2000;121–132.

- Moroz VV, Shatilina TA, Rudykh NI. Formation of anomalous thermal regimes in the northern part of the Tatar Strait and the Amur Liman under the influence of atmospheric processes. Vestnik DVO RAN. 2021;(6):101–110.

- Makhinov AN, Kim VI. The influence of climate change on the hydrological regime of the Amur River. Pacific Geography. 2020;(1):30–39. doi:10.35735/tig.2020.1.1.004.

- Andreev AG. Assessment of the influence of the Amur runoff on the formation of the hydrochemical regime of the Sea of Okhotsk according to satellite measurements. Izv Atmos Ocean Phys. 2020;56(9):1131–1140. doi:10.1134/S0001433820090042.

- Ponomarev VI, Savelyeva NI, Rudykh NI. Variability of the Amur River discharge and the Okhotsk Sea and the Japan Sea physical properties. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on the Okhotsk Sea & Sea Ice. Mombetsu, Hokkaido (Japan); 2005;165–168.

- Makhinov AN, Kim VI, Voronov BA. The 2013 flood in the Amur basin: Causes and consequences. Vestnik DVO RAN. 2014;(2):5–14.

- Makhinov AN, Kim VI, Dugaeva YaYu. Features of large floods of the Amur River during periods of high and low water content. In: Regions of New Development: Current State of Natural Complexes and Their Protection. Materials of the International Scientific Conference. Khabarovsk: IVEP FEB RAS; 2021;178–182.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley