Annals of Environmental Science and Toxicology

Indigenous Advocacy: A Historical Overview of Environmental Movements in India

Department of Environmental Sciences, Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar - 522510, A.P, India

Author and article information

Cite this as

Sasidhar K. Indigenous Advocacy: A Historical Overview of Environmental Movements in India. Ann Environ Sci Toxicol. 2024; 8(1): 068-073. Available from: 10.17352/aest.000081

Copyright License

© 2024 Sasidhar K. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.In the rich tapestry of India’s environmental movements, the threads of indigenous advocacy are woven intricately, embodying centuries-old connections between land, culture, and sustainability. As we embark on this exploration of environmental activism in India, it is imperative to acknowledge the profound role that indigenous communities have played in shaping the country’s conservation narrative. From the verdant forests of the Western Ghats to the arid landscapes of Rajasthan, indigenous peoples have been stewards of the land, safeguarding its biodiversity and ecological balance for generations. Their intimate relationship with nature, rooted in traditional knowledge and spiritual reverence, forms the bedrock of environmental activism in India. This comprehensive paper provides a detailed exploration of the historical evolution, ideological foundations, and transformative impacts of environmental movements in India. By scrutinizing seminal movements such as the Chipko Movement, Narmada Bachao Andolan, and the Appikko Movement, it elucidates diverse strategies, mobilization tactics, and overarching objectives. From Gandhian principles of non-violence to Marxist critiques of capitalist exploitation, the paper navigates through ideological underpinnings, revealing the rich tapestry that has shaped India’s environmental activism landscape. Furthermore, it dissects tangible outcomes and legislative achievements, including landmark environmental laws and the establishment of protected areas. Amidst successes, the paper critically examines contemporary challenges faced by environmental movements, such as conflicts between conservation and development, indigenous marginalization, corporate influence, climate change, and misinformation. Through nuanced analysis, it offers valuable insights into the complex dynamics of environmental activism in India, underscoring its pivotal role in sustainable development.

Environmental movements in India have emerged as potent forces of change, catalyzing societal awareness, policy reforms, and grassroots activism aimed at addressing pressing environmental challenges and advocating for sustainable development practices. From the iconic Chipko Movement of the 1970s to the ongoing struggles against large-scale development projects, these movements have left an indelible mark on India’s environmental consciousness and policy landscape. Rooted in diverse ideological currents, ranging from Gandhian principles of non-violence and reverence for nature to Marxist critiques of capitalist exploitation, environmental movements in India reflect a complex interplay of cultural, social, and political dynamics [1]. This comprehensive paper seeks to delve into the intricacies of environmental activism in India, offering a detailed exploration of its historical evolution, ideological underpinnings, transformative impacts, and contemporary challenges. By analyzing key movements such as the Chipko Movement, Narmada Bachao Andolan, and the Appikko Movement, this paper aims to unravel the strategies, mobilization tactics, and overarching objectives that have shaped India’s environmental activism landscape. Furthermore, it seeks to shed light on the tangible outcomes and legislative achievements catalyzed by these movements, such as the enactment of landmark environmental laws and the establishment of protected areas [2]. However, amidst these successes, the paper also aims to critically examine the contemporary challenges and hurdles faced by environmental movements in India. These challenges include navigating conflicts between conservation imperatives and economic development agendas, addressing the marginalization of indigenous communities, combating corporate influence on policymaking, grappling with the escalating impacts of climate change, and countering misinformation campaigns. Through a nuanced analysis of historical precedents and contemporary realities, this paper endeavors to offer valuable insights into the complex dynamics of environmental activism in India and its implications for sustainable development in the nation.

Role of indigenous in environmental movements in India

Indigenous communities, commonly referred to as Adivasis, have honed agricultural techniques suited to their environments, such as shifting cultivation and terrace farming, which promote biodiversity and soil fertility. Their forest management practices, guided by reverence for nature, include selective logging and rotational grazing to maintain ecosystem health. Additionally, their extensive knowledge of medicinal plants underscores their holistic understanding of the environment. Adivasi cultural rituals, rooted in agricultural cycles and natural rhythms, further exemplify their intimate connection with the earth. In today’s context, as global environmental challenges escalate, Adivasi practices offer valuable insights into sustainable living. Efforts to preserve and integrate indigenous knowledge into conservation initiatives are underway, recognizing its significance for both cultural heritage and environmental sustainability. Ultimately, Adivasi communities embody a profound respect for nature that serves as a guiding light in the quest for a more harmonious relationship with the environment [3].

Indigenous communities in India, like the Bhils, Gonds, Santhals, and Nagas, have long lived in harmony with nature. Their lifestyles and cultural practices are deeply intertwined with the land, reflecting a sustainable ethos passed down through generations. They play a pivotal role in environmental movements across India. With deep-rooted connections to their land and natural resources, Adivasis has been at the forefront of campaigns advocating for environmental conservation and sustainable development. Their traditional knowledge systems, honed over centuries of living in harmony with nature, offer invaluable insights into ecosystem management and biodiversity conservation. Adivasi communities have often led grassroots movements against environmental degradation, asserting their rights to land, forest, and water resources. For instance, in the Chipko Movement of the 1970s, Adivasi women from Uttarakhand famously embraced trees to prevent deforestation, drawing attention to the importance of forest protection. Similarly, in the Narmada Bachao Andolan, Adivasi communities protested against large dam projects that threatened their livelihoods and ancestral lands. Throughout these movements, Adivasis has highlighted the interconnectedness between environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, and social justice [4]. Their resilience, knowledge, and deep-seated reverence for nature continue to inspire and guide environmental activism in India, underscoring the indispensable role of indigenous peoples in safeguarding the planet’s ecological heritage.

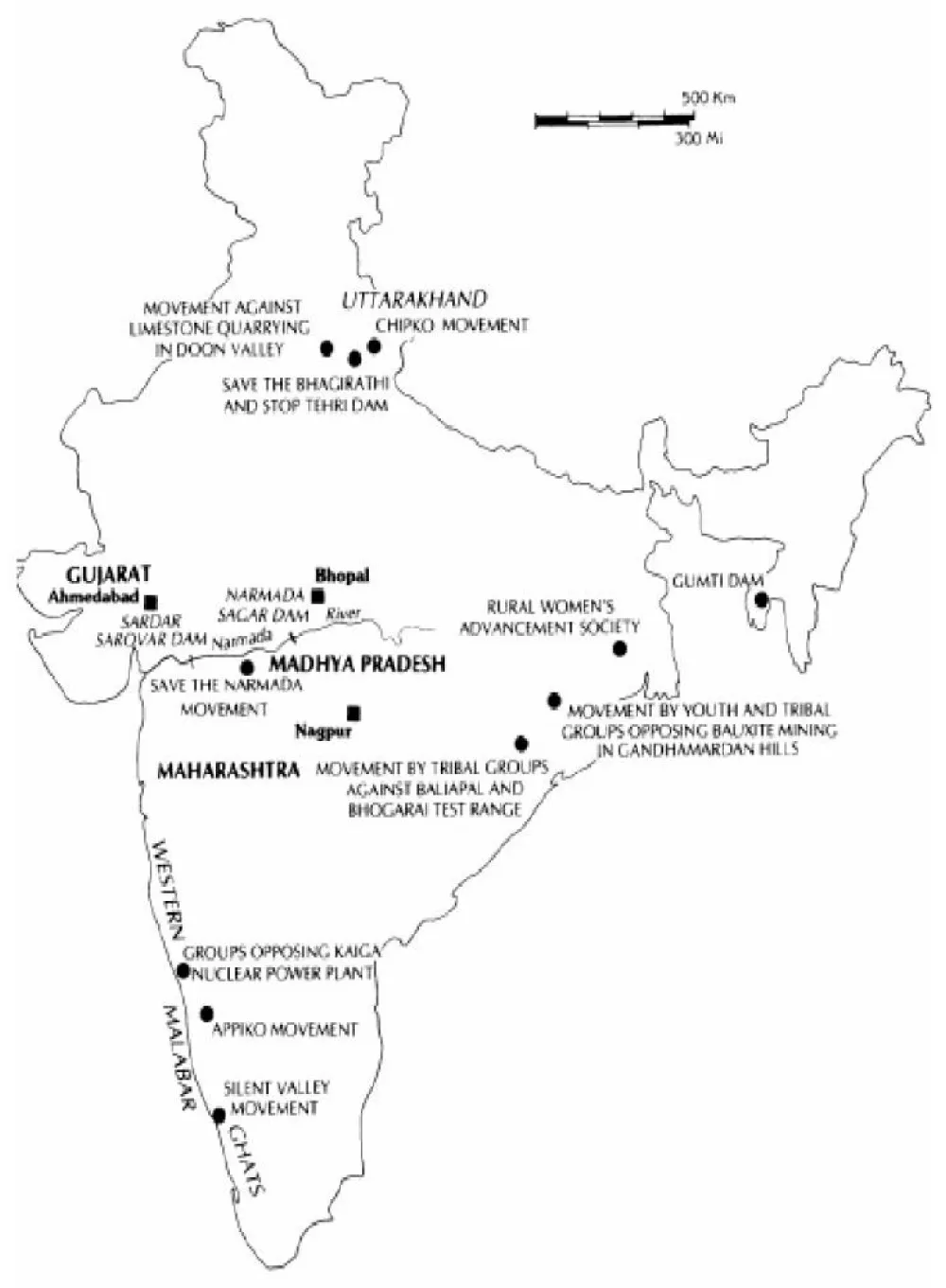

Environmental Movements in India. It highlights various ecological and tribal protests that have taken place across the country, including movements against large-scale industrial projects, dams, deforestation, and nuclear power plants. Map 1 represents various environmental movements in India. Notable movements on the map include:

- Bishnoi Movement in Rajasthan

- Chipko Movement in Uttarakhand

- Appiko Movement in Karnataka

- Silent Valley Movement in Kerala

- The Jungle Bachao Andola in Jharkhand

- Narmada Bachao Andolan against the Sardar Sarovar Dam in Gujarat.

Bishnoi movement

The Bishnoi Movement’s genesis in Khejarli village, Marwar region of Rajasthan in the 1730s, represents a pivotal movement in the history of environmental activism in India. The Bishnoi community, another indigenous group in India, holds a unique position in the country’s environmental conservation efforts. Originating in the arid regions of Rajasthan, the Bishnois are known for their deep reverence for nature and strict adherence to principles of environmental sustainability. The Bishnoi movement was among the first movements to organize in support of environmental conservation, wildlife protection, and green living. Their history is marked by legendary acts of environmental protection, making them iconic figures in India’s conservation narrative. The Bishnois follow the teachings of their founder, Guru Jambheshwar, who laid down principles emphasizing the importance of living in harmony with nature. Notably, in 1730, a Bishnoi woman named Amrita Devi, along with her daughters, bravely sacrificed their lives by hugging trees to prevent their felling, sparking the “Khejri massacre” and compelling the ruler to revoke the order and issue a decree banning tree cutting in Bishnoi villages. The legacy of the Bishnoi Movement endures as a testament to the power of grassroots activism and the imperative of preserving our natural heritage for future generations. By honoring their principles of reverence for nature and collective action, the Bishnoi community continues to inspire environmental stewardship worldwide.

Chipko movement

One of the most iconic environmental movements in India that highlighted the role of indigenous people was the Chipko Movement in the 1970s. Originating in the Himalayan region of Uttarakhand, the movement was led by villagers, predominantly women, who clung to trees to prevent their felling by contractors. This grassroots protest emphasized the dependence of local communities on forests for their survival and catalyzed nationwide awareness about deforestation and environmental degradation. The Chipko Movement, which means “to hug” or “to cling to” in Hindi, began in 1973 in the small village of Mandal in the Alaknanda Valley, Chamoli District. The movement was sparked by the government’s decision to allot forest land to a sports goods company, which would have led to the felling of thousands of trees. Local villagers, who relied on the forest for fuel, fodder, and raw materials, were alarmed by this decision. The leadership of the movement was notably taken up by rural women, including Gaura Devi, a member of the local women’s organization Mahila Mangal Dal, who mobilized other women to protect their forest. The Chipko Movement achieved several tangible successes. It resulted in a 15-year ban on the felling of trees in the Himalayan regions by the then government of Uttar Pradesh, a significant victory for the movement. The movement also spurred the Indian government to rethink its forest policy and laid the groundwork for future environmental legislation. It played a crucial role in shaping India’s environmental policy framework. The Forest Conservation Act of 1980, which aimed to restrict the deforestation of forest lands for non-forest purposes, can be seen as a legislative response to the concerns raised by the Chipko Movement. Moreover, the movement inspired the formation of various other environmental movements across India and the world, fostering a greater sense of environmental consciousness and advocacy for sustainable development. The global recognition of the Chipko Movement underscored the universal appeal and importance of grassroots environmental activism. The movement is celebrated in environmental circles globally and continues to inspire environmentalists and activists who draw on its legacy to champion the rights of indigenous people and the importance of sustainable environmental practices [5,6].

Appiko movement

The Appiko Movement, originating in the Western Ghats of Karnataka in 1983, is a significant grassroots environmental effort inspired by the Chipko Movement in the Himalayas. Led by Panduranga Hegde, it emerged in response to extensive deforestation and ecological degradation caused by commercial logging activities sanctioned by both government and private entities. The forests of the Western Ghats, known for their rich biodiversity and crucial ecological functions, were being depleted at an alarming rate, threatening the livelihoods of local communities who depended on these forests for sustenance and ecological balance. The movement’s strategies were multi-faceted, starting with widespread awareness campaigns to educate villagers about the detrimental effects of deforestation. The movement also emphasized the need for afforestation, soil conservation, and the promotion of sustainable agricultural practices to ensure long-term ecological health. The Appiko Movement successfully influenced policy changes, promoting community-based approaches to conservation and ensuring that local communities were involved in decision-making processes related to forest use and management. The legacy of the Appiko Movement continues to inspire contemporary environmental movements across India, emphasizing the importance of local participation and sustainable practices in environmental stewardship [7].

Saving silent valley movement

The Silent Valley Movement, centered in Kerala, India, is a landmark environmental conservation effort that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. The Silent Valley is a biologically rich 89 sq. km area of tropical virgin forest on the green rolling hills of the Western Ghats. In the early 1980s, a proposal to construct a 200 MW hydroelectric dam on the Kunthipuzha River as part of the Kundremukh project threatened to submerge a significant portion of this valuable rainforest, jeopardizing the habitat of numerous endangered species of both flora and fauna. Silent Valley was home to unique flora and fauna, including endangered species such as the lion-tailed macaque. The project threatened to destroy this biodiversity. The valley’s ecosystem was crucial for maintaining regional ecological balance, including water regulation and soil conservation. The environmental degradation from the dam would have long-term consequences, affecting not just the local ecosystem but also the livelihoods of communities dependent on the forest. The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), an NGO dedicated to environmental awareness and scientific education among Kerala’s masses, spearheaded the campaign to save Silent Valley. The movement served as a comprehensive public education program, significantly raising environmental consciousness and mobilizing public opinion against the dam. The movement’s strategies included campaigns, petitions, and public demonstrations, grounded in non-violent, Gandhian principles.

The Silent Valley Movement remains a seminal example of effective public mobilization for ecological preservation. The movement quickly gained traction, leading to widespread public support and significant media coverage. The protests and scientific arguments reached the state and national governments, compelling them to reconsider the project. In 1980, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi intervened, ordering a temporary halt to the project and commissioning a review by a committee of experts. In 1983, the project was officially abandoned, marking a significant victory for the movement. This decision was not just a triumph for Silent Valley but also a milestone in India’s environmental conservation history. In 1984, the Silent Valley was declared a National Park, ensuring its protection from future development threats. Today, Silent Valley stands as a testament to the enduring impact of grassroots activism and the importance of protecting our natural heritage for future generations [8,9].

The Jungle Bachao Andola

The Jungle Bachao Andola, also known as the Forest Conservation Movement, originated in the Singhbhum district of Jharkhand in 1982. This grassroots movement was a response to the government’s forest policies that threatened the indigenous way of life in the region. Singhbhum, once part of the Chota Nagpur Division of the Bengal Presidency during the British Raj, boasted rich natural forests that sustained local communities for generations. However, when the government proposed replacing these diverse forests with lucrative teak plantations, it ignited a fierce backlash from the tribal inhabitants. Critics of the government’s plan dubbed it “Greed Game Political Populism,” accusing authorities of prioritizing profit at the expense of environmental and cultural heritage. In response, the Jungle Bachao Andola emerged as a rallying cry against the destruction of traditional habitats and the exploitation of natural resources for commercial gain. Tribal communities stood united, vehemently opposing the encroachment on their ancestral lands and advocating for sustainable forest management practices. The movement was more than just a protest; it was a plea for the preservation of ecological balance and cultural identity. By resisting the imposition of teak plantations and demanding the protection of their forests, the tribal communities showcased their unwavering commitment to safeguarding their way of life. The Jungle Bachao Andola serves as a poignant reminder of the power of collective action in the face of environmental injustice, inspiring similar movements worldwide to prioritize people and the planet over profit.

Tehri Dam conflict

The Tehri Dam conflict epitomizes one of the most prolonged environmental struggles witnessed in recent years, revolving around the construction of the towering Tehri Dam, standing at a height of 260.5 meters on the Bhagirathi River in the Garhwal-Himalayas. Advocates of the project tout its potential to generate 2,400 MW of peak power, heralding it as a catalyst for economic growth and urbanization, with promises to establish 140 industrial cities. However, since its inception, the Tehri Dam has been ensnared in controversy, drawing fierce opposition from environmentalists and scientists alike. Despite persistent objections raised by experts of national and international acclaim, the project continues unabated, either unmodified or entirely unimpeded. The roots of resistance against the Tehri Dam trace back to the Tehri Baandh Virodhi Sangharsha Samithi, a coalition spearheaded by the venerable freedom fighter Veerendra Datta Saklani. For more than a decade, this group has staunchly opposed the dam’s construction, citing numerous concerns that strike at the heart of environmental sustainability and social justice. Among the foremost objections is the seismic vulnerability of the region, compounded by the potential submergence of vast forested areas and the displacement of Tehri town, a bastion of historical and cultural significance. Even as construction continues apace, punctuated by sporadic moments of protest-induced delays, the Tehri Dam saga encapsulates the broader tensions inherent in the nexus between large-scale development initiatives and the imperatives of environmental conservation. The standoff serves as a stark reminder of the formidable obstacles faced by grassroots movements in influencing the course of national policy decisions, particularly in contexts where economic imperatives often eclipse environmental considerations. Despite the valiant efforts of activists and the intermittent pledges of governmental review, construction presses forward under the vigilant gaze of law enforcement, underscoring the intricate and often fraught dynamics that characterize the intersection of development agendas and environmental stewardship in contemporary India.

Ideological diversity in Indian environmental movements

Within the multifaceted landscape of Indian environmental movements, Gadgil and Guha (1998) discern five distinct ideological currents that inform the discourse and actions of activists. Crusading Gandhians, drawing upon moral and religious principles, advocate for a return to traditional Indian values, exemplified in movements like the Bishnoi Movement. Ecological Marxists analyze environmental issues through a political-economic lens, addressing socio-economic inequalities as seen in the Chipko Movement. Appropriate Technology Advocates, typified by the Appiko Movement, seek practical alternatives to centralized technologies, rooted in local knowledge. Wilderness Preservationists, represented by movements such as the Silent Valley Movement and Narmada Bachao Andolan, prioritize the preservation of natural habitats and biodiversity against encroachment and development projects. Scientific Conservationists, though less visible in grassroots movements, emphasize evidence-based approaches to conservation. This ideological diversity underscores the rich tapestry of perspectives within Indian environmentalism, each contributing to the ongoing dialogue on sustainable development and environmental justice.

Impact of environmental movements on environmental legislation in India

Environmental movements in India have served as catalysts for legislative action, profoundly influencing the development and enactment of environmental laws that aim to protect natural resources and promote sustainable development practices. These movements, rooted in grassroots activism and public outcry against environmental degradation, have mobilized communities, raised awareness, and pressured the government to address pressing environmental concerns through legal frameworks. One of the most significant examples of the impact of environmental movements on legislation is the Chipko Movement, which emerged in the 1970s in response to rampant deforestation, particularly in the fragile ecosystems of the Himalayan region. The widespread public support and global attention garnered by the Chipko Movement compelled the Indian government to take action. In 1980, the Forest Conservation Act was enacted, imposing restrictions on the felling of trees in forested areas and emphasizing the need for sustainable forest management practices. This legislation was a direct response to the demands of the Chipko Movement and marked a significant step forward in forest conservation efforts in India. Similarly, the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), launched in the 1980s to oppose large dam projects on the Narmada River, highlighted the adverse social, environmental, and economic impacts of such projects on indigenous communities and ecosystems. In response to the NBA’s advocacy efforts, the Indian government passed the Environment (Protection) Act in 1986, which provided a comprehensive framework for environmental regulation and conservation. This legislation empowered authorities to address various environmental issues, including pollution control, conservation of natural resources, and environmental impact assessment of development projects.

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006 further recognized indigenous rights over land and resources, rectifying historical injustices and reinforcing indigenous communities’ role as custodians of biodiversity. Despite legal protections, indigenous communities continue to face challenges from industrialization and infrastructure projects. Movements such as the resistance against the Vedanta bauxite mining project in Niyamgiri Hills and protests against coal mining in Hasdeo Arand forests underscore ongoing battles for environmental justice and indigenous rights. In conclusion, environmental movements have played a pivotal role in shaping India’s environmental legislation, promoting conservation efforts, and advancing sustainable development practices. The voices and knowledge of indigenous communities remain essential in navigating the complex challenges of environmental sustainability and ensuring a greener, more equitable future” [10,11].

Contemporary challenges and issues of environmental movements in India

In recent years, environmental movements in India have faced a multitude of challenges and issues as they strive to address pressing environmental concerns and promote sustainability. Despite significant achievements, such as the enactment of environmental laws and the protection of ecologically sensitive areas, several contemporary challenges hinder the effectiveness of environmental activism in India. One major challenge is the ongoing conflict between environmental conservation and economic development priorities. Rapid industrialization, urbanization, and infrastructure projects often come at the expense of natural habitats, biodiversity, and local communities. Environmental movements must navigate the delicate balance between advocating for conservation measures and addressing the legitimate economic needs of communities, often facing opposition from vested interests and powerful industries.

Additionally, the marginalization of indigenous and tribal communities poses a significant challenge to environmental movements. These communities often bear the brunt of environmental degradation and displacement due to large-scale development projects, yet their voices and rights are frequently overlooked or ignored. Environmental movements must actively work to amplify the voices of marginalized communities and advocate for their rights to land, resources, and cultural heritage. Furthermore, the increasing influence of corporate interests and vested political agendas poses a threat to environmental activism in India. Powerful corporations and industries wield significant influence over government policies and decisions, often leading to the dilution or weakening of environmental regulations and enforcement mechanisms. Environmental movements must confront these vested interests and advocate for transparent and accountable governance to ensure the effective implementation of environmental laws and policies. Moreover, the rise of climate change presents a formidable challenge that requires urgent and collective action. Environmental movements in India must adapt to the changing climate scenario and advocate for mitigation and adaptation measures at local, national, and global levels. Additionally, they must prioritize building resilience in vulnerable communities and promoting sustainable practices that reduce carbon emissions and mitigate environmental degradation [4,12,13].

Lastly, the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation campaigns poses a significant challenge to environmental movements. Misinformation campaigns funded by vested interests seek to discredit environmental activism and undermine public support for conservation efforts. Environmental movements must counter these campaigns by promoting scientific literacy, factual information, and evidence-based advocacy to mobilize public support and drive positive change. Despite these challenges, environmental movements in India have made significant strides in advocating for environmental protection and sustainability. They continue to face numerous obstacles, but by addressing these challenges through collaborative efforts, community engagement, and strategic advocacy, environmental movements can persist in their pivotal role of preserving India’s natural heritage and fostering a sustainable future for generations to come.

Summary and conclusion

Environmental movements in India have been instrumental in raising awareness, advocating for policy changes, and mobilizing communities to address pressing environmental challenges. From the iconic Chipko Movement to the Narmada Bachao Andolan, these movements have brought critical environmental issues to the forefront of public consciousness and catalyzed legislative action to protect natural resources and promote sustainable development. In summary, the recognition of indigenous rights through the enactment of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act in 2006, commonly known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA), is a significant milestone in India’s environmental and social landscape. This legislation represents a crucial step towards rectifying historical injustices faced by indigenous communities and reaffirms their role as custodians of biodiversity and guardians of traditional ecological knowledge.

However, despite these achievements, contemporary environmental movements in India face numerous challenges. Conflicts between environmental conservation and economic development priorities, marginalization of indigenous communities, corporate influence on policymaking, the threat of climate change, and the proliferation of misinformation all pose formidable obstacles to effective environmental activism. To ensure sustainable development and ecological balance, it is imperative to integrate indigenous knowledge systems into mainstream environmental policies. Indigenous communities possess valuable insights into sustainable resource management and ecosystem conservation that can complement scientific approaches. Recognizing and respecting the traditional practices of indigenous communities can enhance conservation efforts and promote a more inclusive approach to environmental stewardship.

In conclusion, while the road ahead may be challenging, the importance of environmental movements in India cannot be overstated. By addressing these challenges through collaborative efforts, community engagement, and strategic advocacy, environmental movements can continue to play a vital role in safeguarding India’s natural heritage and promoting a sustainable future for all. Through their perseverance and dedication, environmental activists have the power to inspire positive change, shape policies, and create a more environmentally conscious society for generations to come.

- Guha R. Environmentalism: A Global History. Longman; 1999. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Hu7DBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT9&dq=1.%09Guha,+Ramachandra.+%22Environmentalism:+A+Global+History.%22+Longman,+1999.&ots=P56RmV7EdH&sig=NYnvXo-49rBUF_2G9CV1iSEtwhY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=1999&f=false

- Shiva V. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development. Zed Books; 1988. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Staying_Alive.html?id=sEG1AAAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y

- McMichael P. The Global Restructuring of Agro-Food Systems. Cornell University Press; 1994. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvv41798

- Sen A. Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press; 1999. Available from: https://www.c3l.uni-oldenburg.de/cde/OMDE625/Sen/Sen-intro.pdf

- Bandyopadhyay J. The Chipko Movement: A Bibliography. Gandhi Peace Foundation; 1985.

- Naik JP. Chipko Movement: Some Aspects. Concept Publishing Company; 1993.

- Guha R. The Unquiet Woods: Ecological Change and Peasant Resistance in the Himalaya. Oxford University Press; 1990. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UHfJLK6g_a8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR10&dq=7.%09Guha,+Ramachandra.+%22The+Unquiet+Woods:+Ecological+Change+and+Peasant+Resistance+in+the+Himalaya.%22+Oxford+University+Press,+1990&ots=f2vYvTAOPM&sig=SQoMhP2oPRdpjLhjj3514TEkuTQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=1990&f=false

- Gadgil M, Guha R. Ecological Conflicts and the Environmental Movement in India. Dev Change. 1994;25(1):101-139. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1994.tb00511.x

- Rangan H. Of Myths and Movements: Rewriting Chipko into Himalayan History. Verso Books; 2000. Available from: https://archive.org/details/ofmythmovements00hari

- Narain S. The State of India's Environment: A Citizen's Report. Centre for Science and Environment; 2019.

- Shiva V. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. South End Press; 1997. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Biopiracy-The-Plunder-of-Nature-and-Knowledge

- Agarwal A, Narain S. Dying Wisdom: Rise, Fall and Potential of India's Traditional Water Harvesting Systems. Centre for Science and Environment; 1999.

- Shiva V. Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply. South End Press; 2000.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley