Open Journal of Environmental Biology

A Review of Enzymes Associated with the Development of African Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) in Palms of Niger Delta, Nigeria

Department of Biology and Forensic Science, Admiralty University, Ibusa, Delta State, Nigeria

Author and article information

Cite this as

Bardi JI. A Review of Enzymes Associated with the Development of African Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) in Palms of Niger Delta, Nigeria. Open J Environ Biol. 2026; 11(1): 001-007. Available from: 10.17352/ojeb.000052

Copyright License

© 2026 Bardi JI. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.The African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) is a coleopteran insect of significant economic and nutritional importance in palm-growing regions of West and Central Africa. It is an important edible insect highly valued for its nutritional and cultural relevance in the Niger Delta. Growing interest in domesticating and rearing this species has increased the need to understand the biological and biochemical processes that drive its development. This review brings together existing research to examine the major digestive and metabolic enzymes that enable R. phoenicis larvae to efficiently feed, digest palm tissues, and sustain rapid growth. Studies on R. phoenicis and related Coleopteran insects consistently identify a diverse array of digestive enzymes, including cellulases, hemicellulases, pectinases, amylases, glycoside hydrolases, and carboxypeptidases, enabling efficient utilization of lignocellulosic and protein components of palm tissues. Structural and protective functions are supported by enzymes such as chitin synthase and laccase, which contribute to cuticle integrity, gut protection, and stress tolerance. Neuropeptide signaling pathways expressed in the gut further regulate feeding behavior, digestion, and nutrient allocation. Collectively, these metabolic features reflect a highly specialized yet flexible digestive system that promotes rapid larval growth and resilience. Understanding these physiological mechanisms provides a scientific basis for optimizing diet formulation, improving mass-rearing efficiency, and advancing the sustainable domestication of R. phoenicis as a valuable food and feed resource.

The African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) is a Coleopteran insect widely distributed across palm-growing regions of West and Central Africa, including the Niger Delta of Nigeria [1]. It is recognized both as a major pest of palms—causing extensive damage to oil palm, raffia, coconut, and other species through larval tunnelling and feeding—and as a culturally and nutritionally important edible insect [1,2]. Rural and urban communities commonly harvest and consume the larvae (“palm grubs”) as a delicacy and a valuable source of protein and lipids [3,4,5]. Nutritional analyses confirm that R. phoenicis larvae are rich in crude protein, lipids, essential amino acids, and fatty acids, supporting growing interest in their mass rearing and commercialization for food and feed [4,5].

Palms, the natural host plants of R. phoenicis, are structurally complex and rich in lignocellulosic components such as cellulose and lignin, which are resistant to enzymatic degradation and pose significant digestive challenges to herbivorous insects [6,7]. Successful larval development within palm tissues, therefore, depends on efficient digestive strategies. Although direct characterization of endogenous cellulases in R. phoenicis is limited, larval growth on cellulose-rich palm tissues suggests the presence of cellulolytic activity within the gut, potentially supported by symbiotic microorganisms [8,9]. Studies of palm-feeding insects have revealed diverse gut bacterial communities capable of producing carbohydrate-active enzymes involved in lignocellulose degradation, indicating that microbial symbionts likely contribute to nutrient acquisition from palm substrates [8,10].

Despite its ecological and nutritional importance, information on the digestive enzyme complement of R. phoenicis remains scarce. Consequently, much of the current understanding is inferred from studies on the closely related red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Research on R. ferrugineus has identified a wide range of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes, including cellulases, pectinases, and multiple glycoside hydrolases, which enable efficient utilization of lignocellulosic and pectic components of palm tissues [10,11]. These findings provide a useful comparative framework for understanding digestion in R. phoenicis.

Overall, available evidence points to a complex digestive system in palm weevils that integrates endogenous enzymes and gut microbiota to exploit structurally tough palm tissues. Understanding this system is critical for the domestication and mass rearing of R. phoenicis, as it informs the development of artificial or semi-natural diets that optimize growth, nutritional yield, and survival while reducing pressure on wild palm resources. In the Niger Delta, where demand for edible insects is increasing, a comprehensive synthesis of existing knowledge on the digestive biology, nutrition, and rearing potential of R. phoenicis is therefore timely. This review compiles current information on digestive enzymes and nutritional attributes, identifies knowledge gaps, and proposes research priorities to support sustainable utilization of this species.

Nutritional composition of African Palm Weevil (APW) larvae

The nutritional composition of African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) larvae exhibits considerable variability across studies, reflecting differences in diet, developmental stage, rearing substrate, and processing methods [12,13]. Numerous investigations have reported the proximate composition of APW larvae, with moisture content ranging from 60.75% [14] to 70.5% [15], which is consistent with broader observations that edible insects typically contain approximately 60–70% moisture, with an average around 65% [16]. Over the past decade, evaluation of protein quality in edible insects has increasingly emphasized amino acid composition rather than crude protein content alone, as amino acid profiles more accurately reflect biological value and nutritional adequacy [16]. Accordingly, the crude protein content of APW larvae has been reported to vary widely, ranging from as low as 8.18% on a fresh-weight basis to as high as 31.05% on a dry-weight basis across different studies [14,16].

Published studies indicate a generally consistent amino acid composition in African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) larvae. Analyses by [15,17] reported comparable levels of key essential amino acids, with lysine and histidine occurring within similar ranges across samples. Nonetheless, variability has been observed for certain amino acids. For instance, [15] documented relatively higher tryptophan levels, whereas [18] reported markedly lower values, a discrepancy likely influenced by differences in larval diet, rearing substrate, and analytical methodology. Despite these variations, comparative assessments suggest that the amino acid profile of R. phoenicis larvae aligns favorably with human essential amino acid requirements, confirming their nutritional relevance as an alternative protein source [18].

Although palm weevil larvae contain chitin, their ash content remains relatively low, with reported values ranging from 0.60% [15] to 5.76% [19]. This variability corresponds closely with differences in lipid content, which has been reported to range from 5.97% [20] to as high as 65.35% [14], emphasizing the importance of lipid analysis in evaluating the overall nutritional quality of APW larvae. Detailed characterization of the lipid fraction reveals that APW larvae contain a mixture of saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Comparable concentrations of C12 fatty acids have been reported by [21] and [22], at 0.21 g/100 g and 0.20 g/100 g, respectively. Notably, PUFA content exhibits substantial variability, ranging from 3.24 g/100 g [17] to 28.00 g/100 g [23]. While SFA contribute to dietary energy, PUFA are more efficiently utilized in metabolic processes and are associated with improved cardiovascular and metabolic health outcomes [24].

Beyond macronutrients, the mineral composition of African palm weevil (APW) larvae shows marked variability across studies. Species-specific analyses have reported relatively high mineral contents, including calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus values of 208.00 mg/100 g, 33.60 mg/100 g, and 352.00 mg/100 g, respectively [22]. In contrast, broader reviews of edible insects have documented substantially lower mineral concentrations in some insect species and preparations, highlighting wide interspecific and methodological variability rather than values specific to Rhynchophorus phoenicis [23]. Such discrepancies reflect the influence of multiple factors, including larval developmental stage, substrate composition, and rearing conditions, all of which are known to affect mineral accumulation in edible insects [25]. Minerals such as calcium and magnesium are essential for skeletal integrity, muscle contraction, nerve transmission, and cardiovascular function, while iron plays a critical role in hemoglobin and myoglobin synthesis and oxygen transport [25]. However, the nutritional contribution of these minerals may be limited by reduced bioavailability, particularly due to the presence of anti-nutritional factors such as phytates and oxalates, which can chelate divalent and trivalent metal ions and inhibit intestinal absorption [25,26].

The capacity of Rhynchophorus phoenicis larvae to accumulate substantial quantities of proteins, lipids, amino acids, and minerals from nutritionally complex palm tissues is ultimately dependent on the functional organization of their digestive system. Efficient liberation and assimilation of these nutrients requires coordinated mechanical processing, enzymatic hydrolysis, and selective absorption along the alimentary canal. Consequently, an understanding of the anatomical structure and functional specialization of the palm weevil digestive tract is essential for elucidating the physiological basis of nutrient utilization, digestive efficiency, and growth performance. The following section, therefore, examines the structural organization of the digestive system, highlighting how its regional specialization supports enzymatic digestion and nutrient absorption in palm - feeding weevils.

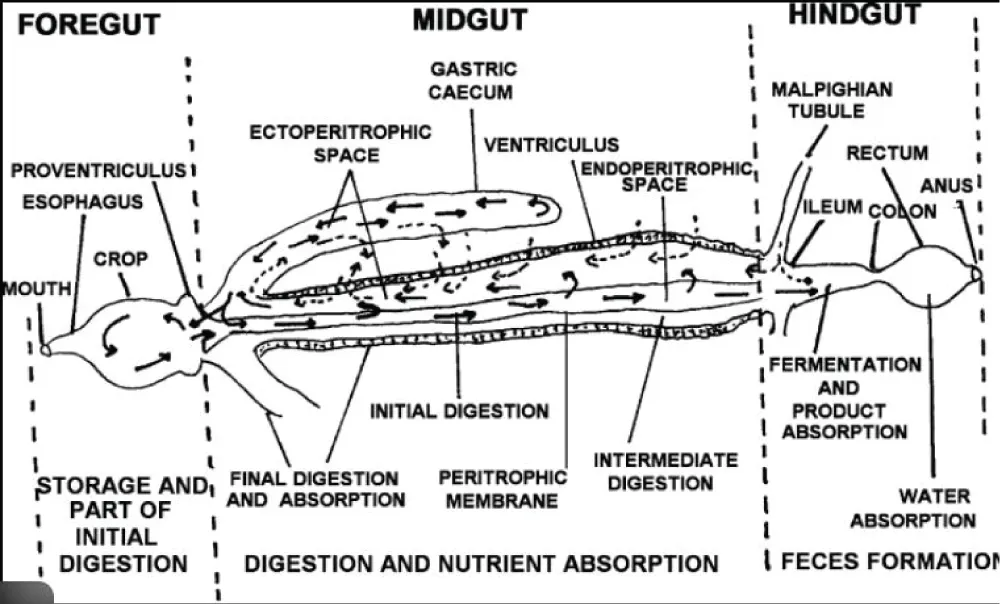

Structure of the palm weevil’s digestive system

The digestive tract is a crucial system in insects, responsible for breaking down food and supplying nutrients required for growth, maintenance, and routine physiological activities [27]. In the African palm weevil (APW, Rhynchophorus phoenicis), the capacity to feed on fibrous palm tissues is supported by both robust chewing mouthparts and a specialized alimentary canal adapted for processing structurally tough plant material. Like most beetles, APW possesses a tubular digestive system divided into three main regions: the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The foregut comprises the mouthparts, pharynx, esophagus, crop, and a well-developed proventriculus.

This muscular structure plays an important role in the mechanical fragmentation of ingested material and may contribute to the initial conditioning of lignocellulosic substrates before they pass into the midgut. In many coleopteran species, the proventriculus bears a cuticular lining armed with sclerotized spines or bristle-like teeth that facilitate grinding and maceration of solid food [27-29].

The midgut is the longest and most functionally significant region of the digestive tract. It lacks a chitinous lining and serves as the primary site for digestive enzyme secretion, nutrient digestion, and absorption. Histologically, the midgut is characterized by a columnar epithelial layer with dense microvilli that increase absorptive surface area, along with intestinal glands and, in some species, regenerative cells or gastric caeca [28]. The hindgut, consisting of the ileum, colon, and rectum, contains distinct rectal pads and functions mainly in the reabsorption of water, ions, and residual nutrients before excretion [27].

Recent studies have demonstrated that palm weevil larvae harbor diverse gut-associated microbial communities with the potential to produce carbohydrate-active enzymes involved in lignocellulose degradation, indicating a synergistic interaction between mechanical processing, microbial activity, and host-derived enzymes that supports efficient utilization of fibrous palm tissues [8]. Morphological differences between developmental stages are also evident, as larval stages typically possess proportionally larger and more active digestive organs to meet the elevated energetic demands associated with rapid growth and repeated molting. This ontogenetic variation helps explain the heightened sensitivity of larvae to disruptions in digestive function and underscores the importance of stage-specific considerations in rearing and nutritional management [7,27]. This anatomical organization provides the structural foundation upon which digestive enzymes and associated metabolic processes operate, as discussed in the following section (Figure 1).

Digestive enzyme systems supporting nutrient assimilation in palm-feeding coleopterans

Unless otherwise stated, mechanistic and enzymatic evidence discussed below is derived from studies on Rhynchophorus ferrugineus and other coleopterans and is used here as a comparative basis for interpreting digestive and metabolic processes in Rhynchophorus phoenicis.

In palm weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), the midgut is specialized for processing lignocellulosic palm tissues rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, starches, and proteins, serving as the principal site of enzyme secretion, digestion, and nutrient absorption. Studies on the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, demonstrate that this specialization supports the production of multiple carbohydrases and proteases essential for palm-based diets [7,30,31]. Given the close phylogenetic relationship and shared feeding ecology between R. ferrugineus and the African palm weevil (R. phoenicis), these findings provide a valuable comparative framework, although direct enzymatic characterization in R. phoenicis remains limited.

At the biochemical level, palm weevil larvae possess a diverse suite of digestive enzymes that facilitate carbohydrate and protein digestion. Partial characterization of digestive proteases and α-amylase in the larval midgut of R. ferrugineus revealed multiple protease activities, reflecting adaptation to protein digestion under varying gut conditions [30]. Such enzymatic diversity is characteristic of herbivorous beetles exploiting nutritionally heterogeneous and structurally complex plant substrates [6,27]. The presence of α-amylase further confirms the importance of starch hydrolysis as a major energy source supporting larval growth.

Carbohydrate digestion is reinforced by glycosidases that catalyze the terminal steps of polysaccharide hydrolysis. α- and β-glucosidases characterized from the midgut of R. ferrugineus convert oligosaccharides into absorbable glucose units and are critical for efficient energy extraction from fibrous diets [31]. β-Glucosidases belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 1 (GH1) are widely conserved in herbivorous beetles and play a central role in carbohydrate digestion and nutrient assimilation [32].

Hemicellulose degradation further enhances palm tissue utilization. Xylanase (EC 3.2.1.8), detected in the gut of palm weevils, including RPW, hydrolyzes xylan—a major component of plant hemicellulose—thereby improving access to fermentable sugars embedded within plant cell walls [33,34]. The combined presence of xylanases, glycosidases, and amylases highlights strong enzymatic adaptation to lignocellulose-rich diets.

Beyond endogenous enzyme production, dietary composition and gut microbial interactions influence digestive efficiency. Changes in feed composition have been shown to alter gut microbiota structure and digestive enzyme activity in insects, illustrating diet-dependent modulation of digestive systems [35]. In palm weevils, gut-associated microorganisms contribute additional carbohydrate-active enzymes, including cellulases and xylanases, which complement host-derived enzymes and enhance lignocellulose degradation [8]. This host–microbe synergy expands digestive capacity beyond the insect’s intrinsic enzymatic repertoire.

Digestive processes in palm weevils also intersect with plant chemical defense mechanisms. Many plant secondary metabolites are stored as glycosylated compounds that influence toxicity and digestibility [36]. In herbivorous insects, enzymes such as β-glucosidases play dual roles in carbohydrate digestion and in the hydrolysis of glycosylated defense compounds, thereby reducing their deterrent effects during feeding [37,38]. In Rhynchophorus species, this enzymatic flexibility likely facilitates sustained feeding on chemically defended palm tissues and reflects a broader co-evolutionary dynamic between plant defenses and insect digestive–detoxification systems [7,37].

Collectively, studies confirm the presence of proteases, amylases, glycosidases, and hemicellulases in palm-feeding weevils, particularly R. ferrugineus, establishing a well-supported model of lignocellulose digestion in this group. However, for R. phoenicis, much of the evidence remains inferential, with direct biochemical and functional validation of contentious enzymes such as endogenous cellulases still limited. The relative contributions of host-derived enzymes versus microbial symbionts therefore remain an active area of investigation [Table 1].

Metabolic and digestive adaptations supporting growth and domestication of the african palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis)

Unless otherwise stated, mechanistic and enzymatic evidence discussed below is derived from studies on Rhynchophorus ferrugineus and other coleopterans and is used here as a comparative basis for interpreting digestive and metabolic processes in Rhynchophorus phoenicis.

The African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) is a phytophagous insect adapted to feeding on moist, woody palm tissues and sugar-rich sap [39]. Like other herbivorous Coleopterans exploiting lignified plant substrates, it encounters diverse plant secondary metabolites that can interfere with digestion and metabolism [40]. Efficient detoxification and metabolic adaptation are therefore essential not only for survival in natural habitats but also for growth performance under domestication and artificial rearing systems [41].

Molecular studies indicate that palm weevils possess a well-developed detoxification system, with cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450) and glutathione-S-transferases (GST) highly expressed in the midgut [34,3,26]. These enzymes constitute key components of the insect detoxification pathway, with CYP450 mediating phase I oxidation and GST facilitating phase II conjugation reactions that enhance solubility and excretion of potentially harmful compounds [42]. Beyond detoxification, these enzyme systems likely contribute to dietary flexibility, enabling palm weevils to exploit palm substrates with varying chemical profiles—an attribute important for feed formulation and domestication [8].

Genome-wide and transcriptomic analyses of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus reveal an extensive repertoire of digestive enzymes, including glycosidases, lipases, and proteases, with many transcripts enriched in gut tissues [23,26]. These include plant cell wall–degrading enzyme families such as glycoside hydrolases and carbohydrate esterases, which facilitate the breakdown of cellulose, hemicellulose, and related polysaccharides during feeding on woody palm tissues. Comparative studies in other wood-feeding beetles, such as Anoplophora glabripennis, similarly demonstrate diverse carbohydrate-active enzyme systems associated with lignocellulose digestion, supporting the inference that R. phoenicis possesses comparable metabolic capabilities.

Proteolytic enzymes also play key roles in palm weevil nutrition. Carboxypeptidases facilitate efficient protein digestion and nitrogen acquisition, supporting rapid larval growth [43]. Chitin synthase, in contrast, is essential for cuticle formation and maintenance of the chitinous gut lining, which protects epithelial tissues from abrasive food particles and ingested pathogens [44,45]. The coordinated activity of digestive and structural enzymes is therefore critical for nutrient assimilation, gut integrity, and overall larval fitness, particularly during periods of rapid growth [46].

Plant cell wall–degrading enzymes, including cellulases, hemicellulases, and pectinases, have also been detected in palm weevil guts [47,48]. These enzymes hydrolyze the major polysaccharide components of palm tissues—cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin—consistent with the palm weevil’s natural feeding ecology and its ability to utilize low-cost, plant-based substrates during domestication [34,49].

In addition to digestive enzymes, neuropeptide precursors and their receptors are predominantly expressed in the gut, where they regulate feeding behavior, digestion, and gut motility [50]. These signaling pathways coordinate physiological responses to diet quality and quantity, ensuring efficient nutrient uptake and energy allocation—processes relevant to optimizing growth under controlled rearing conditions [51].

Collectively, transcriptomic and enzymatic evidence suggests that the metabolic versatility of R. phoenicis arises from integrated endogenous enzyme systems, contributions from gut microbial symbionts, and gene family expansions, including potential horizontally acquired genes [44,52]. Rather than being viewed solely as traits of a pest species, these adaptations represent key biological assets that can be harnessed for domestication and sustainable production. Optimizing diet formulations and advancing gut-focused physiological studies will be central to improving larval performance, growth efficiency, and resilience for food and feed applications [10,37,53-57].

Knowledge gaps and future research directions

Despite growing interest in the African palm weevil, significant gaps remain in understanding its digestive physiology. Direct biochemical characterization of endogenous cellulases, xylanases, and detoxification enzymes in R. phoenicis is still limited, and the functional roles of gut microbial symbionts require targeted metagenomic and enzyme activity studies. Additionally, little is known about the regulation of digestive and detoxification pathways under artificial diets. Addressing these gaps through integrative enzymatic, transcriptomic, and microbiome-based approaches will be essential for optimizing domestication strategies and improving sustainable production.

Conclusion

The African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) exhibits highly specialized digestive and metabolic adaptations that enable it to exploit lignified palm tissues and sugar-rich sap effectively. Detoxification enzymes, gut-associated digestive enzymes, and regulatory neuropeptides collectively support nutrient assimilation, growth, and resilience, while allowing the insect to tolerate chemically defended plant substrates. These physiological traits not only underpin survival in natural habitats but also provide a strong foundation for domestication and mass-rearing efforts. Harnessing this metabolic and enzymatic potential through optimized diet formulation and gut-focused management strategies can enhance growth performance, support sustainable production, and promote the conservation of R. phoenicis as a valuable food and feed resource.

- Commander T, Dimkpa C. Biology and management of the African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) in West and Central Africa. J Pest Sci. 2022;95:1123–1135.

- Egonyu JP, Subramanian S, Omujal F, Niassy S. Edible insects as food and feed in Africa: advances, challenges, and prospects. J Insects Food Feed. 2024;10(1):1–15.

- DeFoliart GR. Insects as human food: nutritional and economic aspects. Crop Prot. 1992;11(5):395–399. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-2194(92)90020-6

- Ekpo KE, Onigbinde AO. Nutritional potentials of the larva of Rhynchophorus phoenicis (F.). Pak J Nutr. 2005;4(5):287–290. Available from: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=pjn.2005.287.290

- Okunowo WO, Afolayan MO, Ajao AM, Oyekanmi AA. Nutritional evaluation of edible larvae of Rhynchophorus phoenicis from different locations in Nigeria. Afr J Food Sci. 2017;11(7):188-193.

- Taiz L, Zeiger E, Møller IM, Murphy A. Plant physiology and development. 6th ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2015. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1752778

- Terra WR, Ferreira C. Biochemistry and molecular biology of digestion. In: Gilbert LI, editor. Insect molecular biology and biochemistry. London: Academic Press; 2012. p. 365-418.

- Habineza P, Niyonzima A, Kim S. Contribution of gut microbiota to cellulose and hemicellulose degradation in palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus spp.). J Insect Sci. 2019;19(4):1–10.

- Omotoso O. Activity of cellulase in the midgut homogenate of the palm weevil, Rhynchophorus phoenicis F. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Acta Sci Intellectus. 2024;2(1):25-35.

- Vatanparast M, Kim Y, Lee JH. Symbiotic bacteria associated with palm-feeding beetles and their role in lignocellulose degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(3):742-752.

- Vatanparast M, Hosseini SA, Rahimi S, Fathipour Y. Functional characterization of cellulases and pectinases in the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;81:39-48.

- Daniel OO, Onilude AA. Production of edible palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) using different agro-industrial by-products. J Insect Sci. 2017;17(1):1–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iew103

- Roos N. Insects and human nutrition. In: Van Huis A, Tomberlin JK, editors. Insects as food and feed: From production to consumption. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2018. p. 83-91. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-292-4_5

- Anankware PJ, Fening KO, Osekre EA, Obeng-Ofori D. Nutritional composition and potential health benefits of the larvae of the African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis Fabricius). J Insects Food Feed. 2021;7(3):379–389. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2020.0083

- Mba OI, Eme PE, Udeozor CC. Proximate composition and mineral content of edible larvae of the palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis). Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2018;3(2):12-17.

- Van Huis A, Rumpold B, Maya C, Roos N. Nutritional qualities and enhancement of edible insects. Annu Rev Nutr. 2021;41:551-576. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-nutr-041520-010856

- Mba OI, Eme PE, Udeozor CC. Amino acid composition and nutritional evaluation of the larvae of the African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis Fabricius). Int J Agric Food Res. 2017;6(4):1-9.

- Olaoye OJ, Ubbor SC. Nutritional quality and essential amino acid profile of African palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) larvae in relation to human dietary requirements. J Insects Food Feed. 2021;7(5):639-648. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2020.0119

- Weru WW, Chege PM, Kinyuru JN, Ochieng JB. Nutritional composition and mineral content of selected edible insects consumed in Africa. Food Sci Nutr. 2021;9(8):4561-4572. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2439

- Quaye B, Afoakwa EO, Abadu B. Nutritional and functional properties of palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus phoenicis) as affected by processing methods. J Food Process Preserv. 2018;42(6):e13612. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.13612

- Mba OI, Eme PE, Udeozor CC. Fatty acid composition and nutritional quality of edible palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus phoenicis). Int J Trop Biol Conserv. 2021;69(2):545-556.

- Amadi EN, Kiin-Kabari DB. Nutritional composition and fatty acid profile of palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus phoenicis). Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2016;1(2):35–41.

- Rumpold BA, Schlüter OK. Nutritional composition and safety aspects of edible insects. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(5):802-823. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200735

- Thomas CN, Dimkpa SO. Dietary fats and fatty acids: implications for metabolic and cardiovascular health. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(4):512-528. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab072

- Idowu AB, Osimani A, Afolayan AJ, Aquilanti L. Nutritional composition and bioavailability of minerals in edible insects. Future Foods. 2019;1-2:100004. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2019.100004

- Ayensu J, Lutterodt H, Annan RA, Edusei VO, Aboagye LM. Anti-nutritional factors and mineral bioavailability in edible insects and insect-based foods. J Food Compos Anal. 2020;92:103545. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103545

- Chapman RF. The insects: structure and function. 5th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. Available from: https://assets.cambridge.org/97805211/13892/frontmatter/9780521113892_frontmatter.pdf

- El-Fattah AA, Abdel-Rahman RS, Hussein MA. Histological and ultrastructural studies of the alimentary canal of palm weevils (Rhynchophorus spp.). J Insect Sci. 2021;21(2):1–10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieab019

- Okorie TG. Comparative morphology of the proventriculus in selected coleopteran insects. J Entomol Zool Stud. 2020;8(3):120-126.

- Abd El-Latif MA. Biochemical characterization of digestive proteases and α-amylase in larvae of the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier). J Insect Sci. 2020;20(3):1–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieaa044

- Darvishzadeh A, Bandani AR. Digestive carbohydrases and proteases in the larval midgut of the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier). J Insect Physiol. 2012;58(3):365–373. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.12.006

- Oppert B, Klingeman WE, Willis JD, Oppert C, Jurat-Fuentes JL, Perkin L. Prospects for digestive protease inhibitors in coleopteran pest management. J Insect Physiol. 2010;56(6):727-737. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.11.020

- Mohamed MA, Ibrahim SS, Abdallah IS, El-Ghareeb DK. Transcriptomic analysis reveals detoxification-related gene expression in the gut of the palm weevil Rhynchophorus spp. Insect Mol Biol. 2022;31(4):456-469. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/imb.12768

- Gao P, Wen Z. Expression profiling of plant cell wall-degrading enzyme genes from the midgut of the wood-feeding weevil Eucryptorrhynchus scrobiculatus. Front Physiol. 2020;11:1111. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.01111

- Chen X, Li J, Zhang Y, Wang H, Li Q. Dietary composition alters gut microbiota structure and digestive enzyme activity in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1178453. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1178453

- Cheng X, Wang S, Xu D, Liu X, Li Y. Glycosyltransferases in plant chemical defense: roles in secondary metabolite modification and stress adaptation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;197:107620. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107620

- Després L, David J-P, Gallet C. The evolutionary ecology of insect resistance to plant chemicals. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22(6):298–307. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.010

- Pentzold S, Zagrobelny M, Rook F, Bak S. How insects overcome plant cyanogenic glucoside defence. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91362. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091362

- Khudri MM, Abdullah MT, Rahman MM, Amin MR. Biology, feeding ecology, and economic importance of palm weevils (Rhynchophorus spp.) associated with palm trees. J Asia Pac Entomol. 2021;24(2):389-397. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2021.03.005

- AlJabr AM, Hussain A, Rizwan-ul-Haq M, Al-Ayedh H. Exposure of herbivorous Coleopterans to plant secondary metabolites: implications for digestion, detoxification, and adaptation. J Insect Physiol. 2017;98:91–99. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2017.01.004

- Jaffar N, Musa M, Abdullahi MM, Sadiq IS. Physiological and metabolic adaptations influencing growth performance of insects under artificial rearing systems. J Insect Sci. 2022;22(4):1-10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieac054

- Hu B, Zhang S, Ren M, Tian X, Wei Q, Mburu DK, Su J. The expression and function of detoxification enzymes in insect adaptation to xenobiotics. Pest Biochem Physiol. 2019;154:18–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.12.001

- Harith Fadzilah N, Nihad M, AlSaleh MA, Bazeyad AY, Pandurangan SB, Munawar K, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of glycosidases, lipases, and proteases from the invasive Asian palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Insects. 2025;16(4):421. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/16/4/421

- Hazzouri KM, Sudalaimuthuasari N, Kundu B, Nelson D, Al-Deeb MA, Le Mansour A, et al. The genome of the red palm weevil reveals signatures of metabolic adaptation and host-associated dietary flexibility. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5615. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19406-7

- Ranganathan S, Govindarajan R, Sriram D. Chitin synthesis, structure, and functional roles in insect gut and cuticle. Front Physiol. 2021;12:643850. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.643850

- Antony B, Johny J, Aldosari SA, Abdelazim MM. Identification and expression profiling of novel plant cell wall-degrading enzymes from a destructive pest of palm trees, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Insect Mol Biol. 2017;26(4):469–484. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/imb.12314

- Rafiei M, Hosseininaveh V, Ghadamyari M, Sajjadian SM. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes, pectinase and cellulase, in the digestive system of the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Plant Prot Sci. 2014;50(4):190-198. Available from: https://pps.agriculturejournals.cz/artkey/pps-201404-0006_plant-cell-wall-degrading-enzymes-pectinase-and-cellulase-in-the-digestive-system-of-the-red-palm-weevil-rhy.php

- Antony B, Johny J, Abdelazim MM, Jakše J, Al Saleh MA, Pain A. Global transcriptome profiling and functional analysis reveal tissue-specific expression of digestive and detoxification genes in Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:440. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5837-4

- Abdel Hameid N. Impact of artificial diets on the biological and chemical properties of the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Braz J Biol. 2022;82(3):614–626. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.264413

- Zhang H, Bai J, Huang S, Liu H, Lin J, Hou Y. Neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae). Front Physiol. 2020;11:159. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00159

- Shi X, Guo Y, Liu H, Zhang L, Wang J. Gut neuropeptides and their receptors: regulators of feeding behaviour, digestion, and nutrient absorption in insects. J Insect Physiol. 2023;145:105444.

- Yang H, Xu D, Zhuo Z, Hu J, Lu B. Transcriptome and gene expression analysis of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) during developmental stages. PeerJ. 2020;8:e10223. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10223

- El Zoghby IRM. Rearing of the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) on different natural diets. Ann Agric Sci Moshtohor. 2018;56(1):509–518. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21608/assjm.2018.214674

- Hussain A, Li Y, Rizwan-ul-Haq M, Al-Ayedh H, AlJabr AM. Role of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and glutathione-S-transferases in insect adaptation to host plant chemical defenses. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2019;158:54-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.4.1411

- Lenka J, González-Tortuero E, Kuba S, Ferry N. Bacterial community profiling and identification of bacteria with lignin-degrading potential in different gut segments of African palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus phoenicis). Front Microbiol. 2025;15:1401965. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1401965

- Seman-Kamarulzaman AF, Pariamiskal FA, Azidi AN, Hassan M. A review on digestive system of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus as a potential target to develop control strategies. Insects. 2023;14(6):506. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/14/6/506

- Siddiqui JA, Khan MM, Bamisile BS, Xu Y. Role of insect gut microbiota in pesticide degradation: a review. J Econ Entomol. 2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.870462

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley